A reporting system for cases of ‘swimmer’s itch’ – a generally harmless but nuisance skin infection found in freshwater – would help raise awareness of the condition and where it has been identified at popular swimming spots, the authors of a recent small-scale study suggest.

‘Swimmer’s itch’, or human cercarial dermatitis (HCD), is a skin infection caused by parasites that live in freshwater snails that can be spread during warm, sunny weather. It causes an unpleasant, itchy rash and skin redness that usually lasts for a couple of days.

Earlier this year, researchers from Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and Budapest Semmelweis University reviewed evidence about the prevalence of HCD in UK rivers, lakes and ponds, and their paper, published in Parasites & Vectors, found only a very small number of previous studies into outbreaks stretching back for almost a century.

Earlier this year, researchers from Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and Budapest Semmelweis University reviewed evidence about the prevalence of HCD in UK rivers, lakes and ponds, and their paper, published in Parasites & Vectors, found only a very small number of previous studies into outbreaks stretching back for almost a century.

However, following media reports of outbreaks of HCD in recent years as open water swimming increases in popularity, researchers argue that it is likely that the prevalence of HCD is underreported in the UK.

And as we approach summer, when open water swimming tends to rise in popularity, they suggest that a reporting system, similar to what is in place in the US for HCD and in the UK for ticks, would help to identify disease hotspots, how prevalent it is, and increase public awareness of ways to prevent the infection.

Dr Alexandra Juhasz, Post-Doctoral Research Associate at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and senior lecturer at the Institute of Medical Microbiology of Semmelweis University, Hungary, said: “Research in this area is scarce. Through our evidence review, we found only eight scientific publications regarding cases in the UK where the presence of HCD was tested and evident.

However, media reports and other sources suggest there have been many more suspected cases across the UK over the past decade. It highlights the need for an official reporting and monitoring system to better understand the prevalence of HCD.

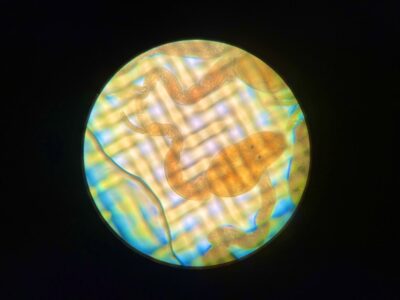

HCD is caused by a parasite, avian schistosome cercariae, first discovered in the US a hundred years ago. The parasite lives and multiplies in freshwater snails before it is released into the water, where it usually infects aquatic birds. It can occasionally instead infect human skin, where the parasite dies and triggers an allergic reaction which causes the redness and an itchy rash.

HCD is caused by a parasite, avian schistosome cercariae, first discovered in the US a hundred years ago. The parasite lives and multiplies in freshwater snails before it is released into the water, where it usually infects aquatic birds. It can occasionally instead infect human skin, where the parasite dies and triggers an allergic reaction which causes the redness and an itchy rash.

Although the skin usually heals in a week without serious complications, secondary bacterial infection can occur, especially in children, who will need antibiotics.

Climate change is also affecting the times, ways and routes that water birds migrate. As these change, so will the areas in the UK where they infect snails.

Orla Kerr, a medical student based at LSTM during the study, said: “We observed that these parasites and the infections typically occur in the summer months, having adapted to the swimming season and benefitting from the generally warmer weather. Owing to the climate crisis and as temperatures increase, a national monitoring system would therefore be even more sensible.”

Photo: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine; Cover: Istock by Getty Images – LeonidKos