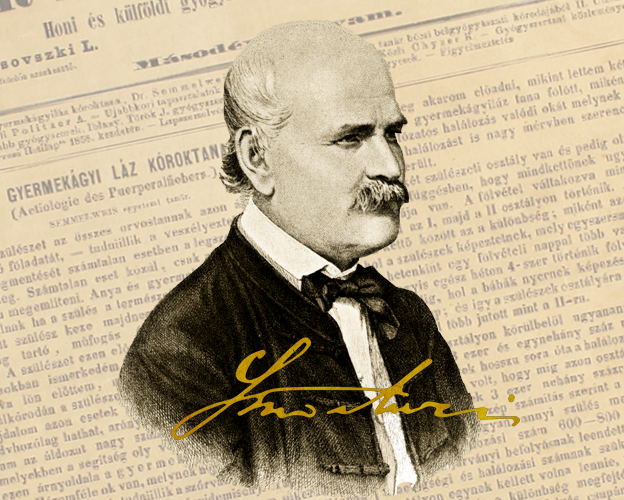

Ignác Fülöp Semmelweis (1818-1865)

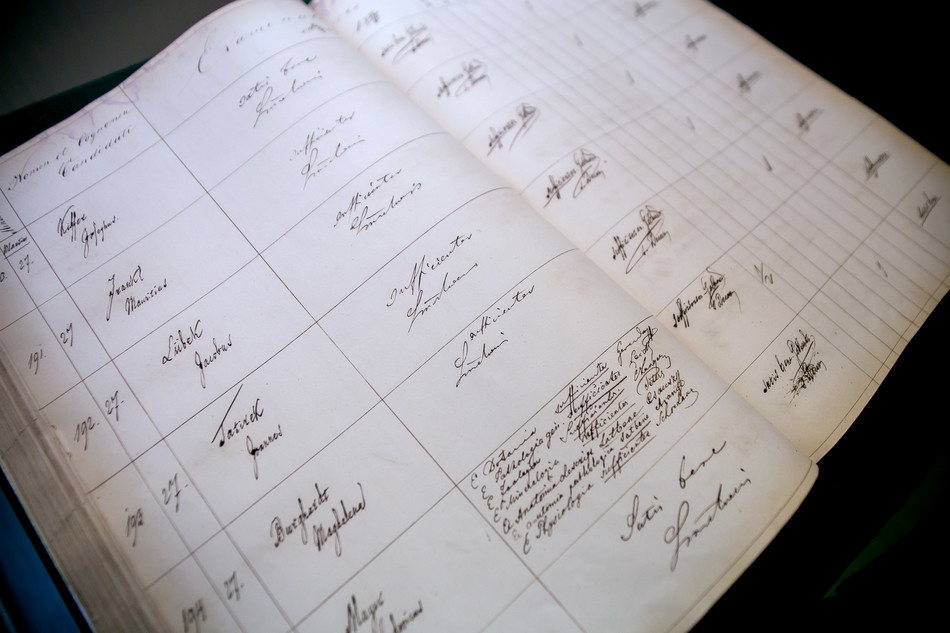

Ignác Fülöp Semmelweis became one of the world’s best-known Hungarian physicians, and “the savior of mothers,” thanks to a discovery he made that was ahead of his time, and which was based on practical observations and conclusions drawn from statistical data. By instructing doctors to wash their hands in a chlorine solution, he was able to dramatically reduce mortality from childbed fever.

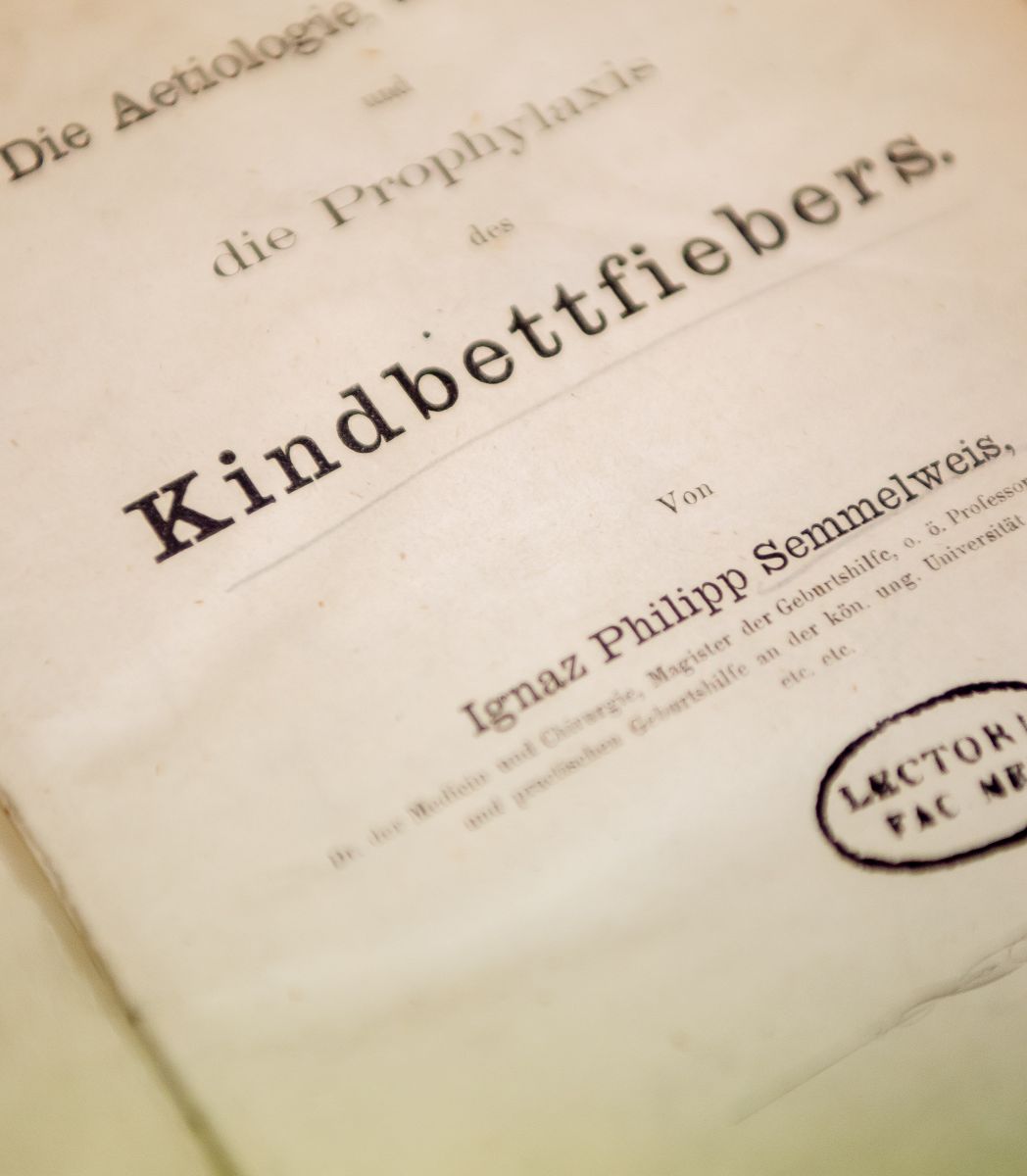

In addition to his revolutionary discovery, which was met with resistance from his contemporary peers, he was also a pioneer in experimental etiology, while he also known for performing the first ovarian surgery and the second Caesarean section in Hungary. He published regularly and was also a strong advocate of obstetrics education.