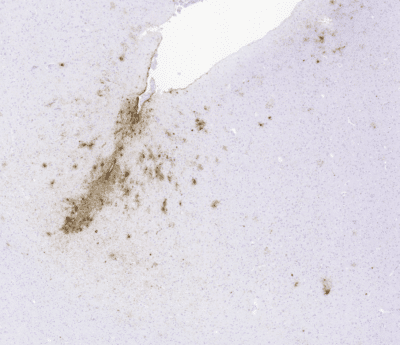

The research, published in Acta Neuropathologica, analysed post-mortem brains from adults aged 41–67, most of them men (29 of 34). Four met the accepted microscopic changes for so-called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and two others had CTE-like changes even if not all features were present in the sampled areas. It is the first confirmation of the disease in a European non-athlete population.

CTE develops after repeated blows to the head and is confirmed only after death by a distinctive build-up of a brain protein called tau. Over time, this damage can be linked to mood swings, aggression, memory loss and movement problems.

First author Dr Krisztina Danics, assistant professor at Semmelweis University’s Department of Pathology, Forensic and Insurance Medicine, said: “Our focus here was to explore pathological brain changes in a very vulnerable, overlooked group expecting to find early forms of more common conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. It was a surprise to discover CTE in people with no elite sport or military background.” She added:

First author Dr Krisztina Danics, assistant professor at Semmelweis University’s Department of Pathology, Forensic and Insurance Medicine, said: “Our focus here was to explore pathological brain changes in a very vulnerable, overlooked group expecting to find early forms of more common conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. It was a surprise to discover CTE in people with no elite sport or military background.” She added:

This supports the notion that repeated head impacts can add up over a lifetime – even outside stadiums.

In the CTE cases, the pattern of brain damage in memory-related regions differed from those seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Other age-related changes were common across the group, and four cases showed another form of neurological disorder usually seen in later life known as argyrophilic grain disease, even though they were relatively young people.

The study was conducted by researchers from Semmelweis University (Budapest, Hungary), the University of Toronto (Canada), and Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia).

The study was conducted by researchers from Semmelweis University (Budapest, Hungary), the University of Toronto (Canada), and Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia).

Before this, similar CTE-related brain changes had been also documented in women in Australia subjected to long-term domestic (intimate partner) violence.

Brain injuries are far more common in homeless people than in the general population, often from falls, assaults, or accidents, and the authors caution that sometimes violent or aggressive behaviour among people experiencing homelessness may be not only a cause but also a consequence of underlying brain damage.

Senior author Dr Gabor G. Kovacs, professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathobiology and Principal Investigator at the Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Disease at the University of Toronto, added: “Seeing CTE in a Central European homeless cohort should change the conversation: it’s not only the disease of athletes, and recognising it matters for care, social services, and even how courts think about behaviour and responsibility.”

Senior author Dr Gabor G. Kovacs, professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathobiology and Principal Investigator at the Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Disease at the University of Toronto, added: “Seeing CTE in a Central European homeless cohort should change the conversation: it’s not only the disease of athletes, and recognising it matters for care, social services, and even how courts think about behaviour and responsibility.”

CTE first entered medical literature in 1928 in boxers, then drew global attention in 2005 when Dr Bennet Omalu reported it in American football player Mike Webster. Their story was later told in the film Concussion starring Oscar-winner Will Smith, who received a Golden Globe nomination for the role. Moreover, initiated by brain pathology studies, guidelines were updated also by the UK soccer league to address the issue of concussion in professional sport.

Co-author Dr Shelley L. Forrest from University of Toronto and Macquarie University said: “Our focus here was disadvantageous socio-economic status rather than genetics. We used strict criteria, including only people who had lived on the street, had no history of professional sport or military service, and whose brains and spinal cords were examined using the same methods – the first such study of a homeless population worldwide. We found CTE in about 12% of the homeless individuals we examined in Central Europe.”

Co-author Dr Shelley L. Forrest from University of Toronto and Macquarie University said: “Our focus here was disadvantageous socio-economic status rather than genetics. We used strict criteria, including only people who had lived on the street, had no history of professional sport or military service, and whose brains and spinal cords were examined using the same methods – the first such study of a homeless population worldwide. We found CTE in about 12% of the homeless individuals we examined in Central Europe.”

According to the international research team, the next step is to develop better tools to detect this disease during life, since routine MRI scans cannot reveal CTE and people affected by it need to be identified and supported sooner.

Photo: Boglarka Zellei, Tamás Kiss – Semmelweis University; Gabor G. Kovacs – University of Toronto; Shelley L. Forrest – Macquarie University; Cover photo: iStock – Yobro10, yodiyim, Srdjanns74