Among all medical schools, why did you choose Semmelweis University to be the one where you start your higher education?

I visited my sister Sophia, who was already studying medicine at Semmelweis. While shadowing her in the basic science departments, I witnessed such an enormous amount of educational experience accumulated that I knew I wanted to study here.

What was your motivation to work in the field of medicine?

By the end of high school, I was highly keen on physics, mathematics, chemistry, and biology. I wanted to know how the body works and I was very curious about circulation.

How did the pre-clinical years in Semmelweis influence your later studies?

Since the early medical school years, we were highly privileged to be tutored by senior faculty. They inspired my passion for in-depth understanding of structure and function. The late Dr. Teréz Tömböl, recognizing my enthusiasm for anatomy, once advised me: “To have a better understanding of anatomy you need to broaden your anatomy studies to other species,” suggesting obviously the need to learn comparative anatomy. Nowadays, in my free time, I often take a walk up in Gower Street to visit the Grant Museum of Zoology in University College London. I am always fascinated by the cardiovascular arrangement of avian and aquatic species, including their circulatory physiology. Receiving excellent gross anatomy lab sessions by Dr. Károly Altdorfer, I enjoyed the histology images from the 38th edition of Gray’s Anatomy and I used extensively the in-house developed Kiss-Szentágothai Anatomy Atlas. I studied every sketch from the neuroanatomy book of Dr. Hajdu – even if I could not read German. I carried on teaching assisting regularly under Dr. Kálmán Majorossy and occasionally under Dr. László Pál Simon. This allowed for a more profound understanding of developmental processes, histology, and fine details of basic science. I have been deeply honored with their friendship. Semmelweis being high yield in medical research, retained a focus in basic science even along the clinical years.

What skills did you develop during your studies at Semmelweis? Is there something you still apply in your day-to-day life that came from these studies?

Firstly, attention to detail and ‘perfectionism’ aiming to in-depth knowledge. Following a successful exam in the first year of my studies, I shared the news of a distinction mark with Dr. Simon. He turned to me, saying: “This is the minimum necessary” for becoming a medical doctor. He was right. This fact was proven throughout my training and later practice. Secondly, being knowledgeable and remaining humble. One needs to be able to communicate with different disciplines of clinical or academic practice. Being humble is the way to be welcomed in other’s fields, learn from them so you succeed the best outcome for your patient. And lastly, work ethic. At the beginning of the working day, I heard several times the phrase “jó munka”. The belief and pride taken from a good day’s work is so important for success.

Please tell us about your volunteering experience you took in during your medical school years. Were there role models, influencing future career choices?

Since the second year of my medical studies, I declared enthusiastically the wish to attend the cardiac surgery operating room in Gottsegen National Cardiovascular Center (GOKVI). This was a high-volume, high-complexity practice. The senior surgical faculty made me feel part of the team. The enormous gap between the surgeons and me at the time, was bridged by my passion for learning and their kindness to have me around and teach. I was extremely lucky to observe revascularization, valve repair and aneurism surgery. I used to spend most of my summer holidays in GOVKI, joining adult cardiac surgery in the mornings and the pediatric cardiac surgery operating room in the afternoons.

After graduating from Semmelweis University, what were the next steps in your career? How did you come across these opportunities?

Following a successful research diploma work at the Városmajor Heart and Vascular Center and my graduation, I joined the residency program in Hungary. Under the mentorship of Dr. Ferenc Horkay, I participated in state-of-the-art cardiac surgery. Additionally, I took every opportunity to watch the vascular surgeons working at Városmajor. I had the opportunity to ‘pick up’ techniques on surgical exposure of peripheral vessels. These techniques became particularly useful in the years to come, both in the field of adult and pediatric mechanical circulatory support. I routinely joined the cath lab of Dr. Béla Merkely. I found myself surrounded by a team of excellent cardiologist-scientists. In this vibrant environment of excellent clinical practice, I learned hemodynamics and treatment of acute phase heart ischemia, rhythm, and intervention. It made me feel confident in communicating with a multidisciplinary team.

In 2010 I was successful in getting a fellowship in the Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals in London. In 2016 I joined the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London. I visited Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School for a short period in 2017, meeting colleagues who were fully focused on excellent practice and contributing to the field. Since 2019 I have remained associated with University College London working in various aspects of research on pediatric cardiac surgery, training of fellows and undergraduate/postgraduate teaching, on projects often associated with Great Ormond Street Hospital.

I have been convinced that translational research is necessary for developing high precision and individualized cardiac surgery, especially when working in a field of rare diseases as pediatric cardiac surgery.

How did you get involved with academics?

Practicing in the highly specialized field of pediatric cardiac surgery, I was invited to support teaching at the University, and instruct in courses at national and international level. I enjoyed the teaching experience a lot and was receiving lots of positive feedback. I got involved in research because I want to find answers to questions that develop along surgery.

As a researcher, what topic do you have your focus on?

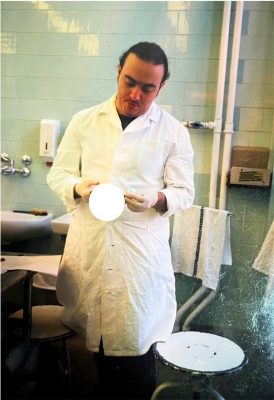

I work on translational research in the field of pediatric cardiac surgery having ongoing projects on a few areas. I use virtual reality (VR) on planning for complex intracardiac repairs of infants, such as intracardiac baffle design and sizing for DORV patients. With the use of 3D printing and computational fluid dynamics, I am working extensively on the development of individualized patches that can be used for augmentation of the aortic arch in neonates including patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. I work on the aortic valve for the development of implantable aortic valve leaflets. I am aiming for designing aortic valve leaflets that resemble the flow dynamics and coaptation area of the native aortic valve leaflet. This can potentially lead to long-lasting repairs for children born with aortic stenosis. We try to use the accumulated experience gained to develop training tools. We also develop 3D printed hearts that can be used on surgical training.

Do you have any advice to current students regarding effective learning, career or how to find balance between their academic and private life?

Try to remain focused along the pre-clinical years. The amount of information is undoubtedly huge, but I can assure that you will keep consulting pre-clinical sciences for all your career. To solve a truly ’complex question’ in the operating room or in the intensive care unit we do not think ’complex’, but rather, we think in terms of physiology, anatomy, pharmacology. And then we get an answer.

Try to get a fair exposure to all aspects of medicine before making a choice into specializing. Aim to carry on with specialist training at a place with a tradition in training. Do not lose contact with science following graduation. Get involved in research. Read original papers and always ask the ’why’, accepting that you will not always get an expected answer. Be thankful for the outliers as much as the points that drop on the curve.

Work-life balance is essential for sustainability and longevity. Try to exercise, stay fit, learn about and enjoy art. It is not only about being great one day. It is about being equally great, every-day and for a long time. Be open to learning from others. Be kind to all.

As you were occupied with many things during your school years – attending cardiac surgery operating room, volunteering, editing textbooks –, would you suggest others to invest their time and energy in these many activities as well? How challenging was it for you?

It was not challenging at all. It felt natural and I can only be thankful I was welcomed and given the opportunity to do it. I loved joining the operating room. I was learning so many new things every day. I wrote the textbooks on topics I was so interested in. I do encourage younger colleagues to invest a bit of their time in visiting clinical departments that they feel they have an interest in.

During your work, what creates happiness for you? What do you view as the biggest positive aspects of your job?

Working on a heart that has not developed the usual way and trying to create a closer to physiologic heart and lung circulation is satisfying. It is such a great privilege to take care of our patients. And it is a great duty as well. We have a duty to maintain excellency while we evolve our practices. It is profoundly rewarding to know that our patients advance in their lives. Operating patients with heart and lung failure and offering heart or lung transplant allows us to witness a miraculous improvement; this is enhancing the call on further developments in mechanical circulatory support, organ donation and transplant medicine. I am happy when I am seeing my research students doing well and them being satisfied by their work. Same applies when I have the chance to instruct and help younger colleagues acquire a new skill in a clinical setting. Joy comes from knowledge, especially when one discovers facts that challenge our current knowledge establishment.

Hanna Szekeres, Alumni Directorate

Photo: Georgios Belitsis