Hyaluronic acid is a viscous, fluid-like substance, a sugar compound that can be found in the skin, the eye and the cockscomb, for example,” said Dr. István Hornyák presenting the path to the patent. The scientific associate at the Institute of Translational Medicine’s Tissue Engineering Laboratory explained that an adult human body contains about 15 grams of hyaluronic acid, which is used in the body to maintain skin elasticity or reduce friction in joints. Very little of it is needed to make a gel as viscous as the 1.6 percent solution they are working with in the lab.

It is also a popular ingredient in various cosmetic products because of its skin rejuvenating properties. Since its human applications have been known for decades, it has been investigated to see how it could help the body’s regenerative processes when replacing tissue deficiencies or in case of surgical correction – but there have also been claims that it could be used to correct certain birth defects such as cleft lip.

In the first stage of the research, hyaluronic acid, as a liquid-soluble compound, was made into a solid, cushion-like spongy material by lyophilisation (moisture extraction by freeze-drying) and made water-insoluble by cross-linking, which met the conditions of the experiment: the aim was to keep the material stable in the organ, because if you just inject native hyaluronic acid, it quickly breaks down and dissolves in the body. Hyaluronic acid alone is not conducive to the integration of cells and tissues, so to promote remodeling, the spongy material was coated with fibrin from blood plasma, which the cells could adhere to and develop. The idea was inspired by a mechanism from wound healing, the suturing that is triggered by surface injuries and facilitated by fibrin. The resulting cushion-like material is the cell scaffold itself. It has been shown in in vitro stem cell experiments and in experimental mice that it provides a suitable environment for cells to thrive and to promote blood vessel formation and thus tissue regeneration.

“One of the most important experiences I had was being involved every step of the way as an idea became a licensed medical device in my hands. It’s a long process, it took about six years, and I succeeded with the help of Hungarian, Austrian, Swedish and Irish partners”

Róbert Tasnádi

Translation: Gábor Kiss

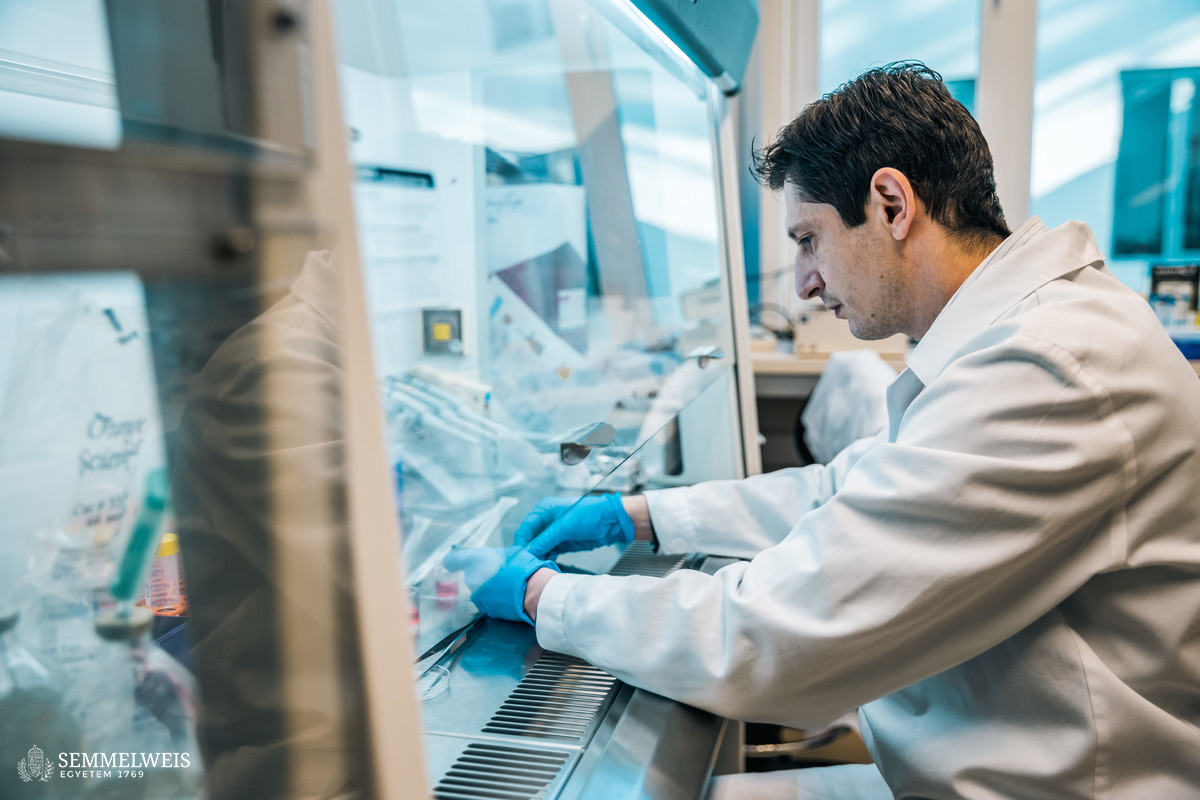

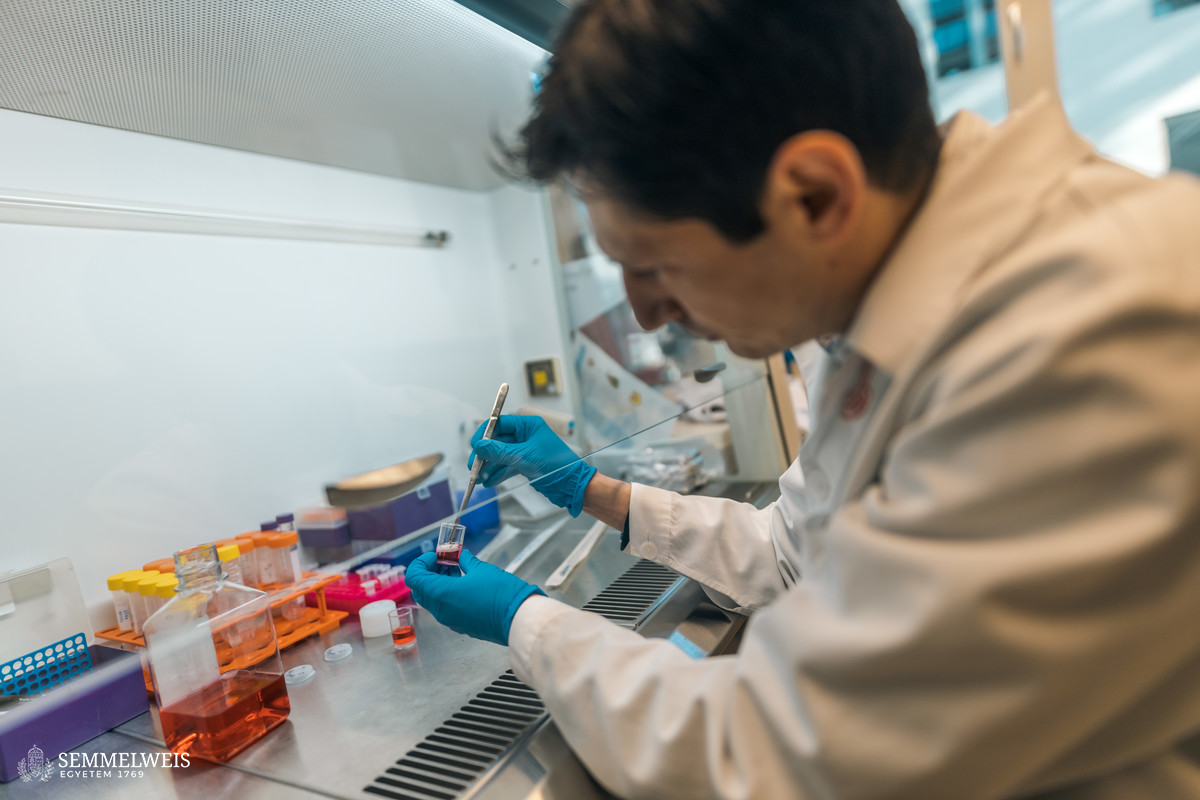

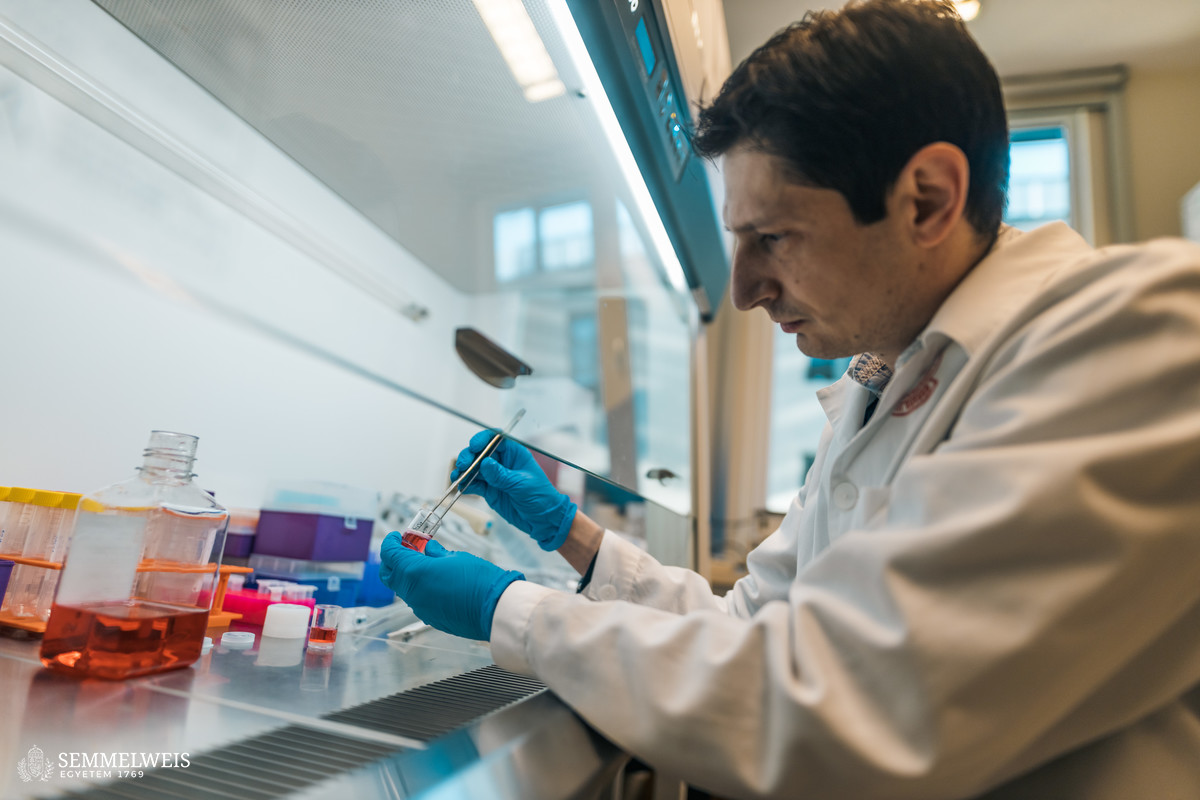

Photo: Bálint Barta – Semmelweis University