“Wednesday, February 1, 1983. It was 40 years ago that the first liver transplant in Hungary was performed at the then 1st Department of Surgery, fighting for the life of a 12-year-old girl. As a schoolboy, I was probably forming letters sitting at my school desk, not knowing that I would have the honour of opening this jubilee conference as the director of the department, where the participants of this historic operation recall their experiences and memories of that time,” Dr. Attila Szijártó, head of the Department of Surgery, Transplantation and Gastroenterology (STÉG) said.

He emphasized that on that day, new hope and history was born in the clinic, which pushed the boundaries of science, just as Professor Thomas Starzl had done almost 20 years earlier when he performed the first human liver transplantation on March 1, 1963 after performing experimental liver transplantation on nearly 200 dogs.

Dr. Attila Szijártó welcomed several members of the then medical and surgical team present at the conference, including Dr. Zsuzsa Szécsény, daughter of the former legendary professor and rector of the university, his granddaughter Anna Rubányi, and Dr. János Weltner, Dr. Maria Tarjányi, Dr. Piroska Antony, Dr. Krisztina Pinkola, Dr. Marianne Borsodi, Dr. Julian Sebestyén. He also welcomed Katalin Karády, Mara Bunford, Ágnes Tantos, Mária Szaniszló and Judit Drabb, assistants who are still working at the clinic, and Vera Tóth and Krisztina Groszman, intensive care nurses.

Although experimental liver transplants in dogs have been performed in Hungary since 1972, the first human transplant in Hungary was still a long time in the making. This involved not only the development of professional protocols for pre- and post-operative procedures, such as the “donor alert” and the duties of the head surgeon, in addition to the considerable experience the clinic had already gained in the management of alcoholic liver haemorrhage patients, but also occasional study trips abroad by members of the medical team. As reported later by Dr. Katalin Darvas, Professor of Anaesthesiology, she had the opportunity to gain a deeper insight into the anaesthesiology of liver transplantation in Cambridge, under the supervision of Professor Roy Calne, prior to the procedure. But Dr. Ferenc Perner, the specialist who performed the first successful kidney transplantation in Hungary on November 16, 1973 at the 1st Department of Surgery of SOTE in Budapest, also highlighted in his lecture how many study trips preceded the successful liver transplantation in 1995.

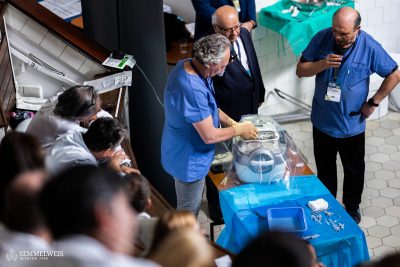

Professor emeritus Dr. Péter Kupcsulik, who participated in the operation, gave a detailed overview of the preparations and the course of the 1983 operation, milestone in the history of Hungarian surgery, with medical data and laboratory results. He also presented a television report from that time, so that in addition to the medical information, the students could also get an idea of how different the operating theatre, the intensive care unit and their equipment are today.

The patient was a 12-year-old girl treated for severe liver failure, resulted by a hepatitis infection at the age of 7. At the time, Dr. Peter Kupcsulik was regularly treating patients with hepatitis at Bethesda Children’s Hospital, which is how he came into contact with the girl who needed a transplant. About a week after parental consent was obtained, it was discovered that there was a 36-year-old brain-dead male donor whose organs were being collected by a team of doctors led by Professor Kupcsulik. Dr. Andor Szécsény performed the transplantation procedure by removing the girl’s liver, while Dr. Kupcsulik performed the arterial and biliary sutures. “In contrast to today’s procedure, the patient received 8,400 millilitres of blood during the 7 hours and 15 minutes of the intervention,” Dr. Katalin Darvas explained, pointing out a significant difference, adding that the girl received about 11 litres of transfusion later on during the post-operative phase.

The operation, performed on February 1, 1983, was technically successful,

The day after the operation the patient was breathing spontaneously and did not need ventilator, from the second day she was feeding orally, she woke up. Her liver function was stable, her bile production started immediately. On the 4-5th day an expulsion reaction appeared, which was successfully treated with Cyclosporin treatment on the 7th day – this was the first use of this new immunosuppressive drug in Hungary. Her liver circulation was still good on day 31, later a bacterial infection appeared, which was only temporarily helped by the antibiotics used. On day 58 there was a deterioration, followed by sepsis and later pulmonary infiltration, and on day 64 the patient died. It was later found out that the girl had a cytomegalovirus infection,” Dr. Péter Kupcsulik explained. At that time, there were no antiviral drugs available at all – the range of anti-rejection drugs was also limited.

He also quoted Professor Szécsény’s statement from the press conference held on the 14th day after the liver transplant: “the first successful liver transplantation in Hungary can be considered a scientific achievement, which proves that many institutions are capable of the highest level of collaboration, which in fact is a hallmark of the quality of Hungarian healthcare.”

Dr. Ferenc Perner gave an overview of the history of organ transplantation in Hungary, mentioning the work of Dr. András Németh who performed the first kidney transplantation. After the operation performed in Szeged in 1962, the patient lived for 79 days. Politics then banned similar operations for about 10 years, but this did not prevent Dr. András Németh from performing 4 more transplants, the professor recalled. In the following decade, the legal framework for organ transplantation was developed, and by the time the kidney transplantation program was organised at SOTE on the suggestion of Professor Andor Szécsény, and the first kidney transplant waiting list was established and the first operation was performed after immunodiagnosis, this obstacle was removed from the path of medicine. This was now an official program funded by the Ministry of Health.

In connection with the successful kidney transplantation in November 1973, after which the patient lived another 26 years, the professor recalled that not only was the imaging equipment that today helps medicine lacking, but there were also difficulties in pre-operative coordination: for example, a member of the medical team gave the post office box number of a village on Lake Balaton.

An important milestone was the resumption of kidney transplantation in Szeged in 1979, followed by the launch of the liver transplantation program of SOTE in the 1980s. After the 1983 operation, three more operations were performed and then the program stopped. From 1991, kidney transplantation departments were opened in Debrecen and finally in Pécs in 1993. Another milestone was the first heart transplantation in 1992 at the Heart and Vascular Center of Semmelweis University thanks to Dr. Zoltán Szabó, and in 1995 the first fully successful liver transplantation at the Department of Transplantation of SOTE – also performed by Dr. Ferenc Perner and his colleagues. The next major breakthrough was the first successful lung transplantation in 2015 at the Breast Unit of the National Institute of Oncology.

Dr. László Piros, Deputy Director of the Department of Surgery, Transplantation and Gastroenterology at Semmelweis University, gave an insight into the future of liver transplantation.

Presenting the transplantation data of the past decades, he drew attention to the importance of joining Eurotransplant, an international organ exchange cooperation that has significantly improved the outlook for patients and increased the number of procedures performed. “In the last week of January, for example, a traumatised liver patient was able to find a liver in 12 hours through Eurotransplant,” Dr. László Piros said.

According to the latest data from the Hungarian National Blood Transfusion Service (HNBTS), in 2022, a total of 369 organ transplants were performed in Hungary at the seven organ transplant centers in four university cities, 313 from deceased donors and 56 from living donors.

At Semmelweis University, 67 liver transplants were performed last year.

In 2022, despite the general shortage of donors, the number of procedures performed started to rise again, thanks to the end of the COVID pandemic, which made donor care in intensive care units more widely available again,” Dr. László Piros emphasized.

However, there are still far more patients waiting for a new liver than there are suitable donor organs available. According to the deputy director, this is partly due to the general shortage of organs, partly to the increasing average age of donors, and partly to civilisation diseases that also have a negative impact on organ quality. The composition of patients on the waiting list has also changed, as the indications for liver transplantation have changed significantly in recent years.

Although thanks to new effective antiviral treatment, the number of liver transplants due to hepatitis C and B virus infections has declined, the number of people on the waiting list for alcoholic liver disease in Hungary remains significant, and the most common indication is biliary tract disease (mainly primary sclerosing cholangitis).

Liver transplantation may also be justified for certain early-stage tumour diseases, notably hepatocellular carcinoma. For the latter, the procedure can be performed only under very strict rules and only if certain criteria are met. In Hungary, liver transplantation for biliary tract cancer is not yet planned, partly because of the difficulty of the Mayo protocol and partly because one of the main problems in Hungary is that the disease is detected too late, even for the protocol.

This type of tumour develops more frequently, even in juveniles, precisely at the site of the aforementioned primary sclerosing cholangitis, so liver transplantation is important in this case not only to treat the underlying liver disease but also to prevent the development of the tumour. For this reason, the MELD score-based classification is not used exclusively for the listing, as it takes little account of the different aspects of tumour recipients in the prioritisation process, in which case patients on the waiting list are also assigned tumour scores. However, this system needs to be continuously updated and improved to take into account changing indications.

Since there are fewer and fewer standard quality livers available, even for splitting, and living donor transplantation is limited, and donation after cardiac arrest is practically non-existent in Hungary due to organisational difficulties and lack of social acceptance,

therefore, the use of mechanical perfusion may play an increasingly important role in the future.

This can sometimes improve the condition of the liver, for example by reducing the fat content, and make the organ more transplantable. “The HNBTS, the Transplantation Section of the Hungarian College of Health Professionals and the Hungarian Transplantation Society are continuously lobbying the Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Health Insurance Fund Management (NEAK) to ensure the purchase and continued funding of a similar perfusion machine (for now for kidney and heart)”, Dr. László Piros added.

At the end of the event, Dr. Katalin Darvas donated the medical records of the first liver transplantation, which she had preserved and collected for the conference, to the Department of Surgery, Transplantation and Gastroenterology. Director Dr. Attila Szijjártó thanked for the documents, which are of museum value, adding that they will be used for educational purposes.

Melinda Katalin Kiss

Translated by Rita Kónya

Photo: Attila Kovács – Semmelweis University