Sleep Medicine Reviews 18 (2014) 435-449

DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.02.001

Piroska Sándora, Sára Szakadáta, Róbert Bódizsa,b,*

a Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Semmelweis University Budapest, Hungary

b Department of General Psychology, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary

* Corresponding author. Semmelweis University, Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Nagyvárad tér 4, 1089 Budapest, Hungary. Tel.: þ361 210 2930×56404; fax: þ361 210 2955. E-mail addresses: bodizs.robert@med.semmelweis-univ.hu, bodrob@net.sote.hu (R. Bódizs). URL: http://www.bodizs-lab.hu

Abstract

The examination of children’s sleep-related mental experiences presents many significant challenges for researchers investigating the developmental trajectories of human dreaming. In contrast to the well explored developmental patterns of human sleep, data from dream research are strikingly divergent with highly ambiguous results and conclusions, even though there is plenty of indirect evidence suggesting parallel patterns of development between neural maturation and dreaming. Thus results from studies of children’s dreaming are of essential importance not only to enlighten us on the nature and role of dreaming but to also add to our knowledge of consciousness and cognitive and emotional development. This review summarizes research results related to the ontogeny of dreaming: we critically reconsider the field, systematically compare the findings based on different methodologies, and highlight the advantages and disadvantages of methods, arguing in favor of methodological pluralism. Since most contradictory results emerge in connection with descriptive as well as content related characteristics of young children’s dreams, we emphasize the importance of carefully selected dream collection methods. In contrast nightmare-related studies yield surprisingly convergent results, thus providing strong basis for inferences about the connections between dreaming and cognitive emotional functioning. Potential directions for dream research are discussed, aiming to explore the as yet unraveled correlations between the maturation of neural organization, sleep architecture and dreaming patterns.

Keywords: Developmental dream research, Children’s dreams, Mental development, Child, Ontogeny of dreaming, Nightmares

Introduction

The major components of the emerging psychological architecture of human beings (psychological functions and processes including sensation, perception, memory and executive functions, etc.) have been shown to be characterized by a specific developmental pattern. The developmental perspective implies to consider dreaming as a mental activity inherently linked to neural maturation, possibly reflecting the changing neural and cognitive processes. Therefore it is highly probable that dreaming can be characterized by a specific psychogenesis as well. The results regarding the sequence of developmental events of dreaming however are strikingly controversial and no sign of a consensus has emerged in the field so far. Even the descriptive level of dream analysis seems to be hampered by methodological difficulties, thus there is no agreement on whether dreams are significantly different amongst age groups and what the specific nature of this difference is. One way to approach the development of dreaming is to investigate sleep itself, which is the natural physiological background state of emerging dream experiences. It follows well determined and specific developmental trajectories [1-3], one could thus infer that the ontogeny of dreaming is governed by the major steps of the ontogeny of sleep. But, this is not actually the case. Although, some remarkable associations between non-invasive indices of several sleep-related physiological processes and formal as well as content-related aspects of dreaming are evident from the literature [4,5], the isomorphism between dreaming and the usual physiological measures of human sleep is a matter of intense debate [6,7]. Here we shed light on some aspects of sleep and neural physiology which we consider as facts with potential developmental relevance, without reviewing the entire field of brainemind isomorphism during sleep. We acknowledge that the cited findings are controversial, but we consider these points as potential start-ups in the investigation of the complex interdependencies between the development of sleep and dreaming. A major breakthrough in the scientific investigation of dreaming was the discovery of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep related behaviors and their associations with dream experiences [8]. REM sleep possibly emerges at a very young age since the neurons responsible for lateral eye movements myelinate at an early stage of fetal development [9]. Later the newborn spends 50% of its sleep time in REM sleep that is proven to be in close connection with the intensive neural development of this age [10]. This fact made some scientists conclude that dreaming also occurs in this early age and that it has a similarly important role in development [9]. Infants’ REM sleep however differs from that of adults both in electroencephalography (EEG) and in behavioral characteristics [11], thus its presence per se does not prove the existence of dreaming. According to some authors the elements of REM sleep gradually merge together throughout pre- and postnatal development to form the more solid and distinct characteristics of adult REM sleep [12]. This could serve as a basis for the idea that dreaming is going through a similar development implying the gradual increase in component cohesion. What we know is that the intensity and vividness of dream experiences in adults are related to the intensity of rapid eye movements during sleep [13,14], this was also shown to be reliable in five- to eightyear-old children [15]. Eye movements during REM sleep are negative measures of actual sleep need [16,17], and correspond to a reduction of dream recall in recovery sleep after sleep deprivation [18]. In accordance with the deeper sleep and increased sleep need in young ages, REM sleep eye movement activity is relatively low in children and is less organized in discrete bursts [19]. Thus, less vivid and less intense dreams, as well as lower dream recall, would be predicted based on this physiological measure. Similarly, EEG coherence during wakefulness was shown to be reduced in childhood, referring to lower neural connectivity due to immature neural organization [20-22]. As REM sleep and wakefulness share many EEG features, the inference that there is a reduced EEG coherence during REM sleep in children has strong indirect support. Since REM sleep EEG coherence was shown to correlate positively with emotions and reports of explicit face imagery in dreams in adults [23], it is reasonable to assume that explicit faces and specific emotions are relatively rare in children’s dreams. On the other hand, high REM sleep theta power, that was shown to predict successful dream recall [24], is known to be high in children showing a decrease during development [25]. Therefore we would expect a higher dream recall rate in children, which not only contradicts the previous assumptions, but numerous empirical investigations as well which suggest a lower dream recall rate in children. The above inconsistencies and scarce correlations of the psycho-physiological approach of dream research suggest that descriptive analysis of dream reports in different age groups has its own merits in increasing the scientific understanding of the ontogeny of dreaming. Naturally there are plenty of methodological difficulties in this field given that dreams are internal experiences that can only be obtained indirectly [26]. Since dream reports are told in the waking state it assumes the ability to remember and verbalize complex inner imagery after the shift between two distinct mental states. Memory and verbal/narrative skills are important mediators between the private experience of dreaming and measurable dream reports. Given that young children tend to refuse to reveal dream material when it is anxious in content [27] or is too different from their waking experiences [28] this problem of indirectness should be taken seriously. Could a child be a dreamer who is waking up in a strong emotional state without verbalizing any experience, or is it only the child who can or is willing to tell a dream? To what extent could dream reports be sleep-related experiences or confabulations of wakefulness? Of course these questions are rather dramatic, exaggerative and somewhat philosophical but help to demonstrate the nature of this problem. Moreover basic uncertainties regarding the methodology still need to be answered: What is the appropriate setting to conduct a study on the ontogeny of dreaming? Should researchers use a laboratory setting or rather a home study? When is the best time to ask the child about the dream? Who has to do the interview? Is it the researcher or is it the parent who has better access to reliable, potentially unbiased information on private experiences, such as dreams? Could only one dream per child provide appropriate data about the dreaming characteristics? (See for example: [29-31]). Given all the above mentioned questions, it is still not clear in what measure the different methods and research results reveal a consistent picture of the characteristic dream experiences of different age groups. In fact the research method chosen seems to have a significant impact on the results and conclusions, so in order to get closer to the answers we summarize scientific results related to children’s dreaming, and systematically analyze the findings based on different methodologies. Our aim is not to compare the different theoretical models of children’s dreaming (for such a review see Appendix A) but rather to give an account of the empirical studies and to critically review the available methods. This analysis is necessary for joining together different approaches of dream research and moving towards a more comprehensive and convergent picture on the development of dreams. It may also serve as an outline for future research with possibly more comparable data across different methodologies and settings.

Dreaming through childhood

Methodology

Reviewing the different data collection methods used in developmental dream studies is of essential importance if we wish to examine the results obtained in different settings with particular age groups. Also we have to be aware of the development of children’s cognitive and emotional skills needed to report a highly intimate and personal dream event, experienced in a mental state distinct from the wakeful state of the dream report. In this section we wish to briefly introduce the different methods and settings used in developmental dream research and to give a short summary about possible confounders affecting dream reports in children.

Methods for collecting dream reports

Observational studies. Observation is a frequently used approach in studies of the first half of the 20th century that focus on dreaming in early childhood [32-37]. These studies aim to infer the inner experience of dreaming from observing the children and the overlap between their daytime and nighttime behaviors. Typically the observer is one of the parents who reports details of the child’s dreams and behaviors to the researcher. Naturally observational studies have many methodological shortcomings: they are neither systematic nor controlled and sometimes rely solely on the parents’ observation reports. On the other hand they provide a very important aspect of dream research; the personal experience and role of specific dreams in one’s life, which quantitative research involving large number of subjects cannot consider (see Supplementary Table S1). Although behavioral observations obviously do not prove the actual dream experience, modern sleep research indirectly supports this method by showing that dream-enacting behaviors are prevalent in healthy subjects and are independent of other parasomnias such as nightmares and sleepwalking [38]. Thus, evidence suggests the close connection between the observed nighttime behavior and reported dream content.

Laboratory studies. The method usually consists of EEG monitoring with systematic REM (and/or NREM) awakenings and instant dream reports to the laboratory assistant personally (3e5 y-olds in Foulkes’ study [39]) or via intercom. The most extensive laboratory investigation series was carried out by David Foulkes including a longitudinal study [29,39] (children from three to 15 y) and several cross sectional ones [40e44]. Laboratory studies are considered the most neutral, unbiased and controlled way of dream collection by Foulkes [29] and many others since his works [45]. However results in dream characteristics especially in case of preschool aged children significantly differ in his laboratory studies from those carried out in other settings (see Table 1). Foulkes’ explanation is that these dream report differences are due to a recall bias towards the exciting and emotionally important memories of morning awakenings and the confabulatory tendency that tends to fill in the gaps in the storyline [42] in both school and home studies. Others point out the possible detrimental effects of the unusual laboratory environment so that children may have difficulties talking about their dreams to the unknown interviewer, the environment may disorient them and cause them to forget their dreams [30] or they may even be inhibited in experiencing the dreams themselves [46]. Moreover, reading through the example dreams collected on nocturnal awakenings, one notices that some of the young children are simply unable to completely wake up for the interview. For example it is obvious from the transcript that Johnny (three-yearand three-month-old), whose dream is the well cited “Fish in a bowl on the riverside”, was half asleep during the interview, which made the interviewer eager to handle the situation and to be more suggestive than necessary. The following is a quote from the interview [Foulkes and Shepherd [47], pp. 24-26]:

“Examiner: Johnny. Hi. What were you dreaming about?

Johnny: (mumbles)

E: What? What were you dreaming about?

J: Fish.

E: What were the fish doing?

[…]

E: What about the dream of fish? What were they doing?

J: Just floating around.

E: Just floating around in the water?

J: Huh.

[…]

E: Were these fish in a river or were they just in a bowl? Like in somebody’s living room.

J: In a bowl.

E: Where was this? Was it in somebody’s house?

J: yeah.

E: Whose house was it?

[…]

J: Just on the side.

E: Was it a piece of furniture? Like on the table?

J: On this side I think.

E: On the side of what?

J: On the side of a river.

[…]”

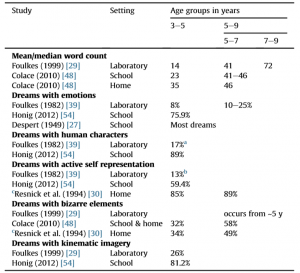

Table 1 Typical differences in results associated with different dream collection methods from preschool to preadolescent ages.

a 17% refers to the percentage of dreams containing family members, other known persons appeared less often and strangers were almost totally absent.

b Percentage of dreams with self movement of any sort.

c In Resnick et al.’s study, age groups correspond to four to five years and eight to ten years.

The lack of full arousal during the dream interview could explain the short and mundane characteristics of Foulkes’ dream reports, as well as the frequent appearance of fatigue and sleep as dream topics (25% of reports) of young children [39]. The phenomenon of unsuccessful arousal from sleep during the night turned out to be a reported confounder in Resnick and colleagues’ study [30], where they wanted to collect dreams in a home setting by systematic nocturnal awakenings, with little success.

Home interview. In a typical home arrangement one of the parents is trained to carry out a structured dream interview with the child upon either spontaneous or scheduled morning awakenings [30,48]. In older ages the child might carry out the interview themselves and tape record them [49]. These are the typical equivalents of written dream diaries of adults, that are sometimes used with children as well, especially under situations where equipment for recording could be difficult to access [50,51]. On the one hand this setting may offer security to the children (home environment, the presence of the parent) and facilitate the process of dream recall; on the other hand some reliability questions arise. Could a parent be a proper interviewer? Parents may feel certain expectations regarding their child’s dreaming [29] and pressure the child to serve the assumed needs. Some authors claim that parents can be reliable interviewers if they receive adequate training beforehand, furthermore recording the entire course of the interview allows the researcher to control their influence on the dream report [30]. Another concern could be the scientific comparability of dream interviews coming from different parents with various personality and relationships with their children.

School interviews. In a school environment (preschool, primary or secondary school) typically a researcher or a caregiver would carry out the interview either individually [48,52-54] or in a group setting [55]. When dealing with very young children (two-year olds) researchers might use rather dramatic means of reporting such as free play sessions [27]. Most authors choosing this method emphasize the benefits of the good relationship between the interviewer and the child, which is free of parental suggestion and expectations toward dreaming, but provides a safe environment. School interviews usually take place over one or two sessions, however some settings allow children to report their current dreams over a period of time [54]. Either way, the major drawback of this method is the time lapse between the interview and the dream experience.

Questionnaires. The palette of questionnaire based assessment is very wide. It is commonly used when the focus of examination is on a specific aspect of dreaming e most typically nightmares and bad dreams [56-60]. It gives an opportunity to request a written account of a specific dream experience, which is typically the “last remembered dream” [61-65]. The questionnaire form is also used to elicit formal characteristics of children’s dreams [66]. Questionnaires are obviously cost effective and allow us to examine large quantities of data. The major drawback here is that the obtained data is indirect and less connected in time to the dream experience making questionnaires potentially less reliable than interview methods. Another dilemma concerns the source of information, which has to be the parent in case of young subjects [59,66]. Evidence shows that parents tend to underestimate the frequency of children’s bad dreams [67], and possibly introduce other biases. Written information can be obtained reliably from children in the preadolescent and adolescent age, however under the age of ten years the “last remembered dreams” data are considered to be less reliable, mostly because children tend to use their waking imagination in creating dream reports [68]. However using an adequate sample size and age group this method is shown to be useful when comparing its results to previous findings [61,69].

Summary. After summarizing the available data collection methods, with their relative advantages and disadvantages, it is obvious that one always has to consider the purpose and focus of their study before selecting the properly suited method (see Supplementary Table S2). When the research focus is on a specific aspect of dreaming (typically nightmares or bad dreams) the most popular choices would be various types of questionnaires [55-57,60,67,70,71]. For estimating dream recall frequency, diaries or interviews on awakening over a period of time were shown to be more accurate than retrospective self estimations in questionnaires [71]. To assess the content of children’s dreams one would most probably choose one of the interview methods. With any method used one has to be careful about the source of information. It seems an unavoidable fact that whoever carries out the interview will influence the nature of the dream report one way or another. Parents may distort the narrative with directed questions; unknown interviewers might stress the child. The environment of the dream report assessment also affects the formal characteristics and content of dreams. The differences between laboratory and home/school setting initiated extensive debate amongst researchers in case of adult samples as well as regarding children’s dreams [30,42,46,72,73]. Two major studies comparing dream content in adults concluded that home dreams were usually more dramatic (containing more aggression, friendliness, misfortune and good fortune) than laboratory dreams [72,74], although their sampling conditions were different (spontaneous morning report vs. night awakenings in the laboratory setting). This difference regarding dream aggression was confirmed later by Weisz and Foulkes [73] using identical sampling conditions in both settings. Although Foulkes [42] in his systematic studies compared dreaming in children under home and laboratory conditions and found no significant difference between dreams from the two settings, results from other studies of young children’s dreams conducted in home [30] or school setting [54] are richer in motion, self representation, human characters and interactions. Foulkes considered the laboratory method the only valid approach to collect dreams, numerous other authors articulated critiques regarding its appropriateness in case of young children, emphasizing the stressing and disorienting effects of the unfamiliar environment [30,46]. Additionally the effect of nighttime awakenings on the content and quality of dream reports of young children has to be mentioned. For a list of dream studies broken down by different dream collection methods see Supplementary Table S3.

Credibility of children’s dreams

Amongst the various methodological concerns that developmental dream researchers face, the evaluation of dream report credibility is a central issue. Characterizing children’s understanding of dreaming as a phenomenon has challenged researchers since Piaget, who claimed that children only achieve a full picture of the non-physical, private, internal nature of dreams by the age of 11 y [75]. Contrary to Piaget’s findings current research from Woolley and Wellman [76] found that children as young as three years old can understand the dreams as being non-physical, unavailable to public perception and internal. These latter findings are confirmed by Meyer and Shore [77], who concluded that four to five year old children increasingly understand that dreams are personal constructions and are not part of the external word. While Piaget found that preschoolers believed that dreams come from outside the dreamer, Woolley et al.’s [78] findings reveal “an impressive understanding of the origin of dream contents by four and five year olds” [p. 27], confirmed by Kinoshita [79] who found that preschool aged children were able to distinguish dream entities from real entities. Similarly young children turned out to be surprisingly good at differentiating between reality and fantasy [80] and even four-yearolds were able to use mental categories to define dreams [81]. The problem of dream report accuracy and possible distortions during recall raise questions about certain cognitive abilities in children. Researchers approach the question of recall from the direction of memory tasks relating to daytime verbal and visual memory performance, with varying results. Although Foulkes [29] did not find any relationship between memory and dream recall frequency, Colace [48] found a correlation between long term memory and the bizarreness of dreams in case of the youngest age group (three- to five-year-olds). Verbal abilities and sociability were found to have a role in report frequency [29] and bizarreness [48,82] in the three- to five-year old groups. However, Foulkes remained skeptical about the reliability of dream reports from children under five years, because gregariousness but not the expected cognitive skills predicted the report rate, and dream report frequencies did not increase with age as expected (in fact threeyear-olds reported more dreams than five-year-olds). Consequently one could assume both memory and verbal skills as possible moderating factors of young children’s dream reports, but as these abilities develop their influence on report frequency or bizarreness diminishes. As language assists children in distinguishing objects and in structuring their perceptual field, verbal and symbolic abilities may also affect dream narrations in a different aspect. According to Bauer [83], the lack of an optimal differentiation between internal representations and objective reality in preschoolers is reflected in their dream descriptions. In his interview-based study preschoolers tended to identify the appearance (or another arbitrary characteristic) of the object as a sufficient condition for them to be regarded as fearful, for example: “His face looked ugly” [p. 72]. Older children tended to specify the aggressive actions and causes in more detail as to why they find an object frightening. This phenomenon may occur as children might not differentiate between symbols from actions or objects they represent. This may explain why most studies found children’s dreams to be particularly short and undetailed, possibly described by only one dream scenario. Especially given that dream report frequency in the youngest age group was correlated with social and verbal skills [29], it is possible that these children just pick a sensible, important or emotionally significant aspect of their dream content when they report their dream narratives (see section “Dreams of preschoolers (3e5 yolds)”, subsection “Nightmares and fears”). On the other hand emotional load in dreams may influence children’s dream narratives also in a negative way. Despert [27], in her nursery-based study, points out that sometimes dreams are heavily loaded with feelings that could not be tolerated in waking life. According to her conclusions this intolerance supposedly has a role in the phenomenon that sometimes children with such dream content will refuse to reveal the dream material. This problem has to be faced when studying children’s dreams and nightmares, especially in young ages and when primary sources of information are the mothers. So far evidence tends to certify children as somewhat limited but still competent dream reporters (for examples see Supplementary Table S1). But the question remains: to what extent does waking fantasy fill in the gaps in the storyline of dreams? This is the question that the researcher has to decide subjectively since, as Foulkes noted [29] “there is no absolute way to verify dream reports, whether those of children or adults” [p. 34]. However researchers should try to establish certain reference points which may help to operationalize this dilemma. In such an effort Colace [48,84] collected eight aspects of the dream reporting process that may be helpful in deciding whether the report is a dream or a product of waking fantasy, although the task is rather difficult since these two might mix up dynamically (for details see Appendix B).

Main results

Preverbal and early verbal dreams (0-3 y-olds)

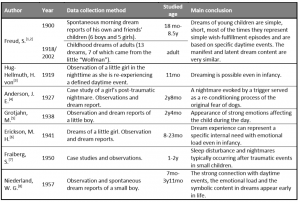

Investigation of preverbal children’s dreams is rather limited, restricted mainly to observational studies based on Freudian theories mostly from the first half of the 20th century (see for review [85-87], see also Supplementary Table S4).

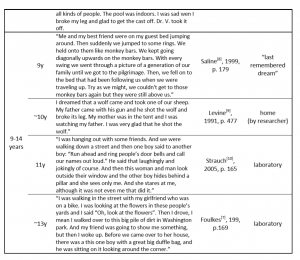

Observational studies. One of the first published observers of children’s dreams was Freud, who based his conclusions on his own and friends’ children’s spontaneous morning dream reports and words spoken during their sleep [34]. According to Freud young children’s dreams are short and simple, are based on experiences from the preceding day, and usually deal with emotions that are intensive or unprocessed reminiscences of daytime events. These dreams are usually free from distortions and bizarre elements until about the age of five. Following Freud’s oeuvre in the early 1900’s, observational studies became popular amongst psychoanalysts. Their main focus was to investigate those questions that Freud left unanswered: when do we start to dream and what nature could the early preverbal dreams have? Numerous authors moved away from Freud’s original idea of dreams having a primary purpose of wish-fulfillment towards the broader concept of re-experiencing emotionally intensive or demanding situations thus helping the dreamer to deal with emotional material. One of these early observations of putative dream experiences in infancy is from von Hug-Hellmuth [88] who recognized the splashing movements and laughter of a nearly one-year-old girl in her sleep as being identical to those of the previous day playing in the pool. Grotjahn [35] observed a two-year-four-month-old boy in his sleep and also his waking life, finding similar overlaps between his activities in the two different states of consciousness. These similarities were also confirmed by the boy’s own verbal reports of his dreams. The author concludes: “.[numerous dreams] would indicate that the child was struggling with strong and strange emotions which he could not work through during the excitement and rapidity of reality” [p. 512]. Other authors also found very close connections between young children’s dreams and their everyday life, emotional events and difficulties (see [32,36]). Some of these researchers thus assumed based on nighttime behavioral indicators that some kind of mental imagery similar to dreaming occurs in children already around one year of age [33,36,88]. One of the first observers, Piaget [37] was somehow more cautious about concluding the presence of mental imagery linked to nighttime behavior patterns. He claimed that the first dreams occur around 1.9e2 y of age, when children are able to confirm their nighttime behavior by telling about the dream in the morning. His observations were supported by a laboratory study, which showed that two-year-olds were able to report their dreams on nighttime awakenings [89]. Similarly the youngest dream reporter in Freud’s family was only 19 mo old when she spoke out in her dream: “Anna F(r)eud, st’awbewy, wild st’awbewy, om’lette, pap!” [34] [p. 110] which Freud accepted and cited as a dream report. Like other dream observations, studies on children’s nightmares and bad dreams also emphasize their importance in emotional processing and development. A good example of this is a case study by Anderson [90], who considers a nightmare of a two-yeareeightmonth-old girl as a reconditioning of a previous fearful experience. The girl had a frightening experience with a black dog one year before the dream, resulting in a fear of black dogs which later disappeared. After a nightmare (triggered by an awake encounter with a dog), her fear reappeared and extended to dogs in general. Here the dream acted as a means of releasing an emotional response that was inhibited in her wakeful life and had the effect of reconditioning the fear reaction. Likewise Fraiberg [33] considered nightmares as one of the symptoms typically appearing following traumatic events during the second year of life.

An early fusion of quantitative and observational research. Despert’s [27] systematic research from 1949 is unique in using individual play sessions as an interview frame. The study involved 190 dreams of 39 children between the ages of two to five years and found that all of the frequent dreamers were amongst the anxious children; however those anxious children, who were inhibited in their daytime behavior, play and imagination, did not report any dream at all. In the collected dreams most of the dominant characters were humans who, if other than parents, were usually put in fearful roles. In Despert’s sample “unpleasant dreams far outnumbered pleasant ones” [p. 170], and she found that two-year-olds mostly dreamt about being bitten, devoured and chased. According to the author dreams serve as an outlet for the discharge of anxiety and aggressive impulses which would not be tolerated during the conscious state. These conclusions also support the possible importance of dreaming in emotional processing. At the same time Despert’s experiences point out an important effect of emotionally loaded dreams to waking dream reports of young children (see section “Credibility of children’s dreams”). Quantitative studies on bad dreams and nightmares in infancy. Two quantitative studies with large sample sizes used parents’ ratings to assess the nature and prevalence of nightmares and bad dreams in infancy [59,91]. The fact that parents’ ratings tend to underestimate the frequency of nightmares, especially in younger ages [67,70], might have caused Simard and colleagues [59] to find a very low prevalence of bad dreams between 29 mo and six years (ranging from 1.7% to 3.6%). In contrast Foster and Anderson’s study from 1936 shows that 43% of the one- to four-year-olds had nightmares during a one week period of parental observation, where any nightmare-associated behavior was noted, such as crying, moaning or showing fear in the night. Simard and colleagues’ longitudinal questionnaire study showed stability in the number of bad dreams over time: the strongest predictor was having bad dreams in the preceding year, up to five years of age. Associations were shown between the child’s emotionally toned experiences, daytime anxiety, anger, fears and worries [91] as well as an anxious or distressed temperament [59] and their nightmares and bad dreams. These results concur with the observational studies discussed above. Foulkes’ contribution to the dreaming of children under three years. Foulkes’s [29] conclusions, although he did not study children below three years of age, are worth mentioning here because of its influence on the field. He found that cognitive visuo-spatial abilities, but neither memory nor verbal skills were in significant and consistent relationship with dream recall frequency throughout the age groups of three- to 15-y-old children. His conclusion was that the maturation of certain cognitive functions especially visuospatial abilities are necessary for dream production thus young children (under the age of three) are not likely to be capable of dreaming at all [92]. This dramatic inference caused an extensive debate amongst dream researchers over the nature of dreaming.

Dreams of preschoolers (3-5 y-olds)

Preschoolers’ dreams, due to verbal improvements, are well studied using various methods including laboratory interviews [29,39-43,92], home dream interviews [30,48], questionnaires [66,93] and kindergarten interviews [27,48,52,54,63,83].

Dream recall and report length. Foulkes in his laboratory studies found the dream reports of three- to five-year-olds to be infrequent (17% of REM awakenings) and brief (average 14 words), usually without a narrative or storyline. Two studies conducted in home setting yielded somewhat different results. In Colace’s [48] study the dreams tended to be longer (mean word count: 35 words). Resnick and colleagues [30] found no difference in dream recall frequency between the fourto five- and eight- to ten-year-old age groups (56% and 57%, respectively). Even though a direct comparison is problematic, because of the differences in dream collection methods, it may be worth looking at the striking difference between 17% of laboratory recall and 56% of home recall within the same age group. Although school interview setting usually does not provide a dream recall frequency measure, studies found children’s dream reports to be “simple” and “short” [27], with an average of 33 words in Honig’s research [54], that tend to be rather similar to those of the home based studies. The only questionnaire based dream study that was not specifically focused on nightmares and bad dreams of children was carried out by Colace [66]. In his parent-recorded questionnaire he assessed dream attitudes, dream frequencies and characteristics of the last reported dream of children between three and nine years. He found that 60% of the three- to five-year-olds reported at least one dream to their parents in the last month. Most of the parents rated their children’s dream reports as being short stories (57.6%, rather than short or long sentences: 32.6%).

General content. Laboratory studies showed that the dreams of young children are rather mundane and simple in their content. Dream reports usually lacked movements, actions (static imagery), an active self character, human characters, interactions and feelings. Instead children frequently dreamt about body-state themes, especially those relating to a sleeping self, and about animals. Typical dreams of this age were “I was sleeping in the bathtub” or “I was sleeping in the co-co stand, where you get Coke from”. According to Foulkes the strikingly barren nature of these dream reports represents children’s habitual dream life rather than spontaneous morning dream reports that are selected by recall bias towards the exciting and emotionally important memories showing dreams much more colorful than they usually are [42]. Regarding home interviews, one of the most striking differences from laboratory studies is the frequency of active self-participation in the dreams, which reached 85% in the younger age group [30]. These results were confirmed by Colace, who found that 68% of the dreams contained an active self in an overall sample of home and school interviews of three- to seven-year-olds [94]. Resnick also found that the most frequent characters in young children’s dreams were family members (29% of all characters) and other known children (28%), contrary to Foulkes who found that human representation was rather scarce in this age group. To illustrate the above, we cite the dream report of a three-year- and six-month-old child: “I dreamed that I woke you up [the mother] and caressed you, gave you a little kiss and hugged you, and then gave a kiss to dad.” [Colace [48], p. 105]. Studies using school interviews agree that most dreams of twoto five-year-olds contain an active self (59.4% [54], 72% among three- to six-year-olds [95]) and human characters (80% [53], main characters were family members in 30%, strangers in 10.5% and friends in 3.5%, while 43% included animal characters [54]), that almost all of them depict motion and activities (81.2% [54]), and that feelings appearing in the dreams are common (in 75.9% [54]). An early school interview study from 1933 examining the wishes, fears and dreams of 400 children concluded that children’s dreams are strongly correlated to their wakeful life and rather reflect the children’s fears than being wish fulfillments [96]. These results confirm home studies rather than laboratory results. Below is the dream report of a three-yearefive-month-old boy who dreams of seeing his deceased grandmother in the form of a soft toy, demonstrating the emotional relevance and the bizarreness that young children’s dreams can include: “I dreamed the bunny and the she-bunny, now the she-bunny was grannie and she was with C [the boy’s younger sister] and the blue bunny was with me.” [Colace [48], p. 171]. Colace’s parental questionnaire study [66,97] showed that dream characters are most frequently family members (present in 60% of the dreams), active self-representation is predominant (56%), social interaction is frequent (in 67.4% of all reported dreams) even in young children’s dreams. Aggressive content was rare (in 17.9% of the dreams), which might be explained by the parent’s possible bias towards presenting more pleasant dreams.

Dream bizarreness. In Foulkes’ laboratory studies the question of dream bizarreness was addressed by the measures of character and setting distortion, by which means he found no bizarre elements in young children’s dreams. Another study (using narrative analyses), based on the school interview of 369 children, found that in the course of three to five years of age dream narratives have an increase in conflict content and a decrease in non-conflict and realistic content [98]. Though Colace and colleagues [48] found most of young children’s dream reports being ordinary and realistic (68% on average across his school and home based studies), still 32% of these dreams showed some level of strange and/or bizarre content. In his studies, Colace used his own measure of bizarreness based on Freudian principles [99]. Similarly, in her home based dream research Resnick also found that 34% of the reports contained bizarre elements among the four- to five-year-olds using Hobson’s rating system [100]. As for the questionnaire studies, Colace found that the majority of the dreams (55.4%) contained some strange elements (38.2%) or bizarre and improbable content (16.2%). The remaining 45.6% of the dreams was “ordinary and realistic”. It is interesting to note that amongst the three categories of bizarreness (discontinuities, incongruities, and uncertainties) used in Resnick’s study, uncertainties were totally absent among preschoolers, while in the older age group it counted for one third of the bizarreness scores. Possible hints for the relative absence of bizarre elements [29,30,48], and especially the lack of uncertainties [30] in young children’s dreams lie in Bauer’s observation of undeveloped symbolization (see section “Credibility of children’s dreams”) and also as DeMartino [28] points out, in the possible failure to report material in their dreams that are contrary to their own experiences.

Nightmares and fears. Muris and his colleagues [52] interviewed children in their schools and found that typical scary dreams of preschoolers are about imaginary creatures, personal harm and animals. In Hawkins and Williams’ study [93] frequent nightmares turned out to be associated with fears of going to bed, night terrors, snoring and sleep talking, but showed little or no relationship with life events and behavioral problems. Bauer [83] aimed to depict developmental patterns in children’s fears, including frightening dreams, by interviewing children between four and 12 y of age. 74% of the preschoolers (4-6 y-olds) reported having scary dreams. Preschoolers tended to have fears of imaginary creatures and poorly defined phenomena, whereas 10-12 y-old school children reported much more specific and realistic fears, involving body injuries and physical danger. The same pattern of children’s fears was described in Jersild’s [96] study, who also found (similarly to Hawkins and Williams [93]) that children’s unpleasant dreams reflect these subjective fears, rather than their objective life experiences. Since the nature of fears and bad dreams seem to be closely connected, the above mentioned pattern of fears might be linked to children’s dream reports through linguistic and symbolic development, as described in the “Credibility of children’s dreams” section.

Children’s dreams in primary school age (5-9 y-olds)

In this age range, as children develop in their cognitive skills, their dream reports become more and more reliable [29], making it possible to assess dreams written directly by the children [51,63,64].

Dream recall frequency and report length. According to Foulkes [29], the strongest dream quality changes occur around the ages of seven and eight, when the children’s dream reports get more frequent (43%) and become significantly longer (median: 41 words), showing more complex narrative structure. In this age group dream recall frequency was correlated reliably with visuo-spatial skills, which lead Foulkes to conclude that the development of this domain makes dreaming possible. Surprisingly Foulkes contradicted his previous findings with adolescents [41], and claimed that dream recall frequency was not associated with the adjustment of waking anxiety, thus concluded that it is not personal problems or conflicts that prompt children’s dreaming, rather it is the cognitive competencies that allow them to be more accomplished dreamers. Some of Foulkes’ results are confirmed by home and school based studies as well. For example Colace also found an increase in the narrative complexity and dream report length compared to three- to-five-year-olds (median: 41-46 words), although this is a modest increase compared to the laboratory results. On the contrary, during his questionnaire study he did not find increase in dream report length, presumably because the five-level scale filled out by the parents did not turn out to be sensitive enough for detecting fine differences (parents most commonly chose “short stories” to describe their children’s dream report lengths). Oberst [64] collected dream accounts using the “last remembered dream” method from 120 children aged seven to 18 y. She found that the mean dream report length amongst the seven- to eight-year-olds was 70 words, which is higher than that of the above mentioned studies, but also her age range is narrower.

General content. In Foulkes’ laboratory studies the greatest improvement around the age of eight is the first appearance of active self-representation together with thoughts (10% of all reports) and feelings in dreams. He also observed kinematic imagery and social interactions for the first time in dreams collected between five to seven years. In contrast, Resnick found no significant difference in active self representation between her four- to five(in 85% of the dreams) and eight- to ten-year-old (89%) age groups. Oberst’s [64] results with the “last remembered dream” method indicate that gender differences characteristic to the adult population [69] start to emerge even in her youngest age group (7e8 y) and develop throughout adolescence to adulthood. She found that boys tend to dream more about male characters, whereas girls have a more balanced character ratio (male/female character ratio: 79% and 38%, respectively), and for most of the groups boys show more physical aggression and aggressive interactions (aggression/character index: 61% for boys and 24% for girls). All aggression variables were highest in the youngest age group (60e87% of dreams contained at least one aggressive interaction), who were also more often victims than aggressors in their dreams (victimization in 87e 90% of all dreams with aggression); both tendencies decreased with age.

Bizarreness in dreams. Distortion in characters and settings or bizarreness was still quite rare between five and nine years in Foulkes’ studies. In contrast Colace [48] found that almost half of the children (47%) between five and seven reported relatively complex dream narratives and 58% of the reports contained at least one bizarre element. Bizarreness in the dream reports correlated with various cognitive abilities (linguistic skills, attention span, symbolization and visuo-spatial skills) and superego development (according to Freudian structural theory [34]). Superego development was measured by performance in situational stories about social normativity [48]. Colace’s school based studies yielded similar results. He concluded that the developmental achievement that allows dreams to show a highly bizarre narrative can be present at the age of five: “There was a horse, it was all green with red eyes, so this horse took mum, [.] she was the horse’s wife [.] my eyes became red because I was the daughter of these two people, . of this horse and of this and of . mother” [dream report of a five-yeareten-month-old girl, Colace [48], p. 120].

Nightmares and trauma. Assessing the relationships between waking life and nightmares Li and colleagues [60] found that frequent nightmares were associated with a constellation of child, sleep and family related factors, such as comorbid sleep disturbances, parental predisposition, child hyperactivity, mood disturbances and poor academic performance. Extreme conditions in waking life, such as war trauma, have a distinctive effect on children’s dreams, as high levels of aggression and death scenes appeared in dreams of children reported in an early study conducted during the First Word War [63]. Helminen and Punamäki [51] also found a strong effect by examining the dreams of Palestinian children from traumatic and non-traumatic environments between the ages of six to 16 y. They found enhanced dream recall (mean dream recall in the trauma group: 4.13 versus non-trauma group: 2.89) with more contextual images (90% versus 74%) among the highly traumatized children. Exposure to severe trauma was usually associated with a higher level of posttraumatic symptoms and a high intensity of negative emotional imagery in dreams, however this was not the case for the children in the trauma group whose dreams incorporated highly intense positive emotional imagery. This relationship between the emotional processing of traumatic events and dreams is also shown in the dreams of children who have suffered road traffic accidents [101]: between two and six months post-accident, the incidence of posttraumatic nightmares decreased in parallel to the decline in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Similarly Terr [102], dealing with children who had been kidnapped, found that all of the children had had dreams about the traumatic event, including unremembered night terrors (60% of the children), exact repeat dreams (52%), modified playback dreams (52%) and disguised dreams (17%) that incorporated symbolically some aspects of the event. He found that those children who had good abilities to verbalize their feelings tended to have more variety of dreams related to the trauma, had more memories of their dreams and could use their associations to gain relief in their psychiatric interviews. Studies assessing nightmares and bad dreams of school aged children emphasize the association between feelings, emotional regulation, coping mechanisms and dreams, and conclude that dreams are correlated with [60,91] or even promote emotional processing and work-through [51,83,102].

Dreaming in preadolescence (9-14 y-olds)

In the pre-adolescent age questionnaires and written dream accounts are the most popular dream collection methods, since they provide the easiest way to collect a large amount of data from numerous participants (see section “Methods for collecting dream reports”).

Dream recall frequency and report length. Foulkes found that between the ages of nine to 11 dream report frequency of REM awakenings reached a median of 79%, close to the typical adult data (85e90%), with both report frequency and length becoming stable individual parameters for each child. Together with these changes, visuo-spatial skills, although still associated with report frequency, had relatively less influence on dreaming than other personal/social variables, similarly to adults [29]. According to another laboratory based study by Strauch [103] children still continue to report more dreams upon night awakenings between the ages of 9e15 (increase from 77% to 82% for girls and from 58% to 74% to boys). Strauch, in her home based study [49], where children had to tape record their own verbal dream recalls, found report length improve from an average of 100 words to 141 words from nine to 15 y of age. Soffer-Dudek [71] in her seven-day dream frequency log-based longitudinal study of children aged ten to twelve found an average of one dream recalled in every second night. She also observed a distinct decreasing tendency in girls dream report frequency over the years.

General content of dreams. According to Foulkes’ findings in this age range dreaming starts to reflect personality; for instance children who frequently dream of an angry self, display hostility during the presleep period as well. Along with personality, gender roles seem to be reflected in dreams starting at preadolescence [104]. An interesting pattern that arises among the 13e15 y-olds is that a number of the REM dream reports seem to lose some of the achieved vividness, kinematic characteristics, social interaction, busyness and narrative complexity, and become more similar to the simpler non-REM dream reports. This phenomenon, together with the lower report rate (73%) compared to the 9e11 y-olds, could be connected to ongoing neural changes (synaptic pruning) in the adolescent age, as Soffer-Dudek also hypothesizes based on similar recall frequency patterns in her questionnaire based work [71]. Similarly in her laboratory study, Strauch [103] found an almost continuous increase in dream report frequency from 9e15 y, with a slight relapse from 79% in the 9e11 to 74% in the 11e13 y age group for girls. Other aspects of her findings (both in the laboratory and in her home study [49]) are in line with Foulkes’ results: gradual appearance of active self, increase in social interactions, inclusion of speech and relative scarceness of feelings associated with dreams. Overall aggression/friendliness percentage declined for boys (70% at 9e11 y) and increased for girls (36% at 9e11 y), arriving at around the same level at 11e15 y (51% and 61% respectively). All children tended to be victims of aggression rather than being aggressors. Similarly, in 10e12 y-old girls’ dreams (collected from www. DreamBank.net [68]) McNamara and colleagues found that a high percentage depicted the dreamer as a victim. Moreover, a high self negativity together with low self agency (the latter measured by dreamer involved success percent: 35% compared to 63% of adults) was also reported for this age group [105]. Findings using the “last remembered dream” method show many similarities with laboratory studies [61,62,65], most interestingly about aggression and gender differences that become more prominent in the preadolescent age [62,65]. Dream contents like aggressiveness, inhibition of aggression, friendliness and dream emotions were shown to correlate with personality traits such as neuroticism and extraversion in a dream content questionnaire-based study of 107 preadolescent students [106].

Bizarreness. Dream bizarreness seemed to change continuously throughout the age range [103]: bizarre or unlikely dreams (lacking any relation to the waking world) decreased with age (from 31% to 15% of all dreams), but inventive dreams (combining waking experiences in an unusual manner) increased (from 29% to 44%) showing the development of higher level cognitive skills, as separate waking memories had to be combined into new entities.

Nightmare studies. Dream diaries are typically used to assess the dreams of children living under traumatizing conditions. Punamäki and colleagues [50,51,107] found that children who had waking traumatic experiences reported more unpleasant, mundane, and fragmented dreams involving death and destruction themes, with typical feelings of anger, anxiety and hostility. Bilu [108], examining Israeli and Arab children’s dreams found similar results: children living closer to disturbed areas or the “enemy” had significantly more “encounter dreams” involving meeting characters from the other side pervaded with aggression and overt violence. Valli et al. compared the dream logs of Kurdish children and adolescents (9-17 y-olds) severely traumatized by Iraqi military forces with similar data derived from non-traumatized Finnish children. Significantly higher number of dreams and threatening dream events were evident in the dream reports of the traumatized children. Moreover, the dream threats of traumatized children were also more severe in nature than the threats of less traumatized or nontraumatized children [109]. Levine [110], however, studying Irish, Bedouin and Israeli children’s dreams, found that culture and norms had a stronger effect on dreams than the closeness or exposure to conflicts.

Questionnaire based nightmare and bad dream studies typically show that nightmare frequency is highest between the ages of five to ten [60,111,112], and is related to other sleep disorders [56,60], trait anxiety [56,57,113], emotional problems [67,70,71], accumulated stress in wakeful life [56] and behavior problems [60,114]. The strongest predictor was having nightmares at a previous testing time [59,70]. Similarly to questionnaire based findings [59,70], Foulkes also found that the frequency of unpleasant dreams became stable within this age span, so that the number of such dreams between nine to 11 y also predicted the same prevalence five years later. Although nightmares are shown to be a stable feature of childhood, investigations may show some influence of television watching on aggressive and scary dreams [115]. It is still not clear if nightmare frequency is affected by television or whether bad dreams take up the program content, but nightmare content seems to change with the popular scary figure of the time [116].

Adolescent dreams (14-18 y)

Since we aimed to focus on the developmental aspects of dreaming we do not discuss adolescents’ dreams here because they are rather similar to those of the adults’, considering both research methodologies and results. As an end of the gradual increase during childhood, dream report characteristics in adolescence including gender differences tend to arrive to the same level as that of the adult population [64], presumably reflecting stronger socialization effects [117].

Summary and conclusions

Looking at the available data on children’s dreams it is obvious that different dream collection methods often result in highly variable and sometimes even contradictory outcomes. Studying young children’s dreams the number of available methods is restricted, this age group shows the most diverse results, probably due to higher sensitivity to different environmental conditions and research settings. In this segment we aim to highlight the most important results on and discuss the relevant aspects of children’s dreaming, to draw implications for present dream theory and guidelines for future research.

Children’s dream reports

Given the numerous controversies in the field it is surprising that children’s dream narratives being short and simple (compared to those of the adults) is a feature that has been confirmed by several authors [27,29,37,48,66] after the first report by Freud [34]. The few studies comparing the report lengths of different age groups yielded somewhat different results. Foulkes found a gradual increase in report length and narration throughout childhood concluding to reflect gradually-achieved developmental steps [29,39]. Colace also found difference in report lengths between three- to five- and five- to seven-year-olds’ narratives [48] in his home and school based studies but in the questionnaire based one he concluded that even preschoolers are able to form a short story of their dreams rather than just a sentence [66] similarly to five- to seven-year-olds. Behind these results one can observe the contradiction of laboratory versus home, school and questionnaire studies. When talking about narrative characteristics of dreams, we have to be aware that we can only be familiar with a secondary verbal expression of the original dream experience. In fact some authors claim that short and undetailed dream narratives could be a result of incomplete symbolization skills in young children [83] not necessarily reflecting the whole experience itself.

Preschoolers may only mention for example the ugliness of a dream character, and no other details that may be implied in the experience (for example experiencing threat, feeling fear, etc.), which would reflect the child’s verbal and symbolization skills rather than dreaming abilities. Others note that dream emotional tone could affect the likeliness of dream reports [27]. Given the inconsistent findings of children’s memories in connection with stressful events [118], it is hard to ascertain in what way emotional load in dreams would affect dream recalls, although it is reasonable to assume that it does therefore further research in this aspect is necessary. Finally as we observe the possible causes and confounders of dream report characteristics (implemented in the methodology and in the developmental level of children), we may conclude that deriving strong conclusions about children’s dreaming is premature at this point. A good example here could be Foulkes claiming validity only for laboratory studies and concluding perhaps prematurely that children under a certain age are not capable of dreaming.

Bizarreness of children’s dreams

Methods used for depicting bizarreness in children’s dreams, vary on a wide scale from simply detecting character and setting distortion [47] to applying complex multifaceted scales [100], thus drawing a direct comparison between the results could be highly problematic. In spite of these differences it is noteworthy that, contrary to Foulkes’ findings [39], which assumed no bizarreness in preschoolers’ dreams at all, others found a noticeable proportion of dreams with bizarre content (32% [48], 34% [30], 55.4% [66]). These results show that even young children are capable of the mental representation of bizarre or improbable events in their dreams (see Table 1), though this proportion is significantly lower than that of adults [30]. On the other hand these dreams of young children reinforce that bizarreness is not an inherent characteristic of REM dreams (therefore cannot exist solely as a consequence of random neurophysiologic phenomena of REM sleep as predicted by the activationeinput sourceemodulation (AIM) model [119]. In fact some findings suggest that cognitive development is also involved in achieving bizarreness in dreams. Colace [48] revealed associations between certain cognitive skills and dream bizarreness in children aged three to seven, and Resnick [30] demonstrated how different categories of bizarreness dominate in certain age groups suggesting parallelism with cognitive maturation.

Dream content and methodology

As we have seen above, the characteristics and content of children’s dreams observed by different studies seems to become more divergent with decreasing age. Approaching infancy there are fewer objective methods to investigate the nighttime experiences of the child. Consequently we still have no answer to the fundamental question: does dreaming exist in preverbal ages? Hypotheses about infant dreaming are formed indirectly: investigations on neural development [9,45] and observational case studies (for reviews see [85-87]) suggest dream experiences at these early ages; however inferences from cognitive psychological studies based on the dreaming of older children [29] predict the lack of dream experiences before the appropriate functioning of the visuo-spatial skills. The investigation of kindergarten-aged children produces a great variation in the data. Laboratory research reveals that the dreams of this age group are rare and mundane, with no emotions, no human characters or active self-representation, no kinematic imagery or narrative storyline [29]. In contrast, qualitative observational data show that young children’s dreams, in spite of being short and simple, depict a great variety of daytime experiences and have a strong connection with the child’s emotional struggles [34,36,90]. Quantitative outcomes of interview studies cohere with these latter findings suggesting that young children’s dreams are kinematic, filled with various human and non-human characters, depicting scenes of central and active self-participation [27,54]. Dream researchers agree that most of these differences are caused by the different methodologies and settings, but there has been a huge debate on which method yields the most representative results regarding young children’s dreams [29-31,42,46] (see also Supplementary Table S2). According to Foulkes the only reliable way of investigating dreams is in the neutral laboratory environment, which is free from parental suggestions, memory distortion and confabulation [29], although his results left some researchers with doubts [30,120]. Researchers with different methodological preferences blame the strange and unknown laboratory environment for posing a possible disorienting or restricting effect on the children (see section “Methods for collecting dream reports”) [30,46]. There is no doubt that the dream reports of children before adolescence are shorter and simpler than those collected from older children and adults. However, the static nature of young children’s dreams, as well as their lack of human characters, emotions and active self-representation was probably overestimated by the leaders of the laboratory studies [29]. If we consider the special features of narrative behavior in preschoolers (verbalizing only one relevant aspect of a story), together with the relative lack of differentiation between internal and external events [83] and the arbitrary nature of reporting anxiety dreams at all [27], the situation becomes even more modulated. As the gap between the results revealed by different methodologies seems to be much larger in young children than in any other age groups, the issue of the simplicity of children’s dreams has to be treated cautiously and analyzed critically. In conclusion, we do not wish to speak against the laboratory setting, instead we wish to emphasize that this method has its own drawbacks and advantages in a similar proportion as other settings. Every method will have a certain influence on the data and determine the results to a certain extent as dreaming is a physically and/or emotionally unique experience for each individual. Therefore we suggest that instead of searching for the most neutral or natural way of dream collection, or the typical “baseline dreams” of different age groups, one should consider any setting and method as a confounder on dreaming. Certainly different methods suit different research projects and aims more than others [120], we conclude that each of the described methods has its own relevance to developmental dream research. We believe that methodological pluralism leaves space for experiencing the spectrum and potentials of children’s dreams.

Nightmares and emotional processing

Importantly, nightmare studies converge on recognizing the role of emotional processing in dreaming throughout the lifespan. Early observational studies and later quantitative and qualitative research, using interviews, questionnaires or diaries, concluded that nightmares and bad dreams are closely connected to traumatic events [50,101,102,121], affective coping [51,122] or nighttime emotional reprocessing [90,123] in childhood as well as in adulthood, and this overarches different cultures [108,110]. Several studies demonstrated that the frequency of nightmare recall can be a correlate of current emotional difficulties (for example PTSD symptoms [101], anxiety levels [41,57,59] or exposure to trauma [121] or loss [124]) and that long-term emotional states and coping strategies are also reflected in certain dream characteristics [51,57,102]. The hypothesis that dreams have a role in reorganizing and reprocessing emotional experiences, is also a key concept in later neuro-cognitive theories supported by evidence from modern neuro-imaging techniques. Levin and Nielsen [123,125,126] emphasize the cooperation between subcortical areas conveying affective information and frontal-cognitive functions alleviating intense affective stimuli during dreaming. According to their model, the insufficient functioning of this affective-cognitive dialog may result in nightmares and in the long term it has a major role in developing and sustaining the recurrent nightmares in PTSD. An extensive review [112] concluded that the prevalence of nightmares in children is highest around the age of six to ten, decreasing thereafter. Some authors also found that nightmare occurrence is most common in childhood and adolescence through young adulthood and then declines with age [126]. Since frontal lobe functions are supposed to control and alleviate emotional loads during REM sleep and are among the last brain parts to fully develop [127], a plausible explanation lies in the immature nature of frontal executive functions. This hypothesis is supported by a recent finding showing impaired executive functioning characteristic for nightmare sufferers [128]. These coincident findings, showing a pattern of parallel progress in neuro-cognitive changes and dream patterns, draw attention to the need for further investigations regarding the correlations between these two related fields and to the importance of merging both adult and developmental dream literature.

Towards an extended neuro-cognitive dream theory

A number of empirical work on young children’s dreams support the hypothesis that developmental dreams deal with general emotional issues of the children rather than being simple wish fulfillments as Freud claimed [34] (see Appendix C). We suggest that interpreting dreams from the broader perspective of emotional reprocessing during the night is more understandable and plausible considering modern dream theories and could easily include the category of wish fulfillment (presented in Appendix C). For instance Freud’s example of little Hermann, who was asked to give the cherry basket to Freud, was probably having an emotional battle inside whether to obey to the adult order or do what comes naturally to a 22-mo-old: to eat the cherries. When he dreamt about eating all the cherries the next night he probably managed to re-process all his negative and unjust feelings towards the adults who forced him to give up on the cherries. If we consider all these everyday emotional turbulences and negative feelings of children, it is plausible to assume that they need some sort of re-processing or “extinction” in a way as Nielsen and Levin [123,126] suggest in their neuro-cognitive dream concept. Though the authors present their theory mainly by approaching the issue from nightmares and bad dreams as being indicators of problems in emotional regulation, their idea could be applied to dreaming in general. We should mention however, that the Freudian concepts on the function of dreams as guardians of sleep and as “safety valves” can be considered as forerunners of the fear extinction/emotional reprocessing theory of Nielsen and Levin [123,126]. Moreover, recent attempts to synthesize psychoanalysis with neurosciences are increasingly successful in reinterpreting Freudian concepts on children’s dreams. According to a new study emerging from this background child’s dreams often fulfill a wish originated in recent daytime, where it was associated to an intense affective state. Through the hallucinatory fulfillment, the dreams apparently resolve the associated affective state (the “affective-reestablishment” hypothesis) [129]. We suggest that developmental dream research gives an opportunity to support and to expand Nielsen and Levin’s theory on dreaming by further explaining the associations of neuro-cognitive changes and dream development. This inclusive hypothesis could lead us to the first step towards a unified neuro-cognitive dream theory on a conjoined basis of adult and developmental dream and nightmare research, incorporating dreaming over the lifespan.

Future directions for research

In order to clear up the confusingly diverse results from dream research of preschool children we need further investigation into the nature and characteristic of children’s dreams using carefully selected methods as well as a critical attitude when considering the inherent shortcomings of the research project. After obtaining a more coherent picture of the attributes of children’s dreams, the clarification of the cognitive, psychological, neural and sleep-EEG correlates of dream reports can be initialized. Preliminary and interesting results arise from the studies of Foulkes [29] on the correlation between dreaming and visuo-spatial development, or on the lack of correlation between memory performance and dream recall. Moreover, Colace [48] was able to demonstrate the correlation between general mental development and dream bizarreness in children. These preliminary results are encouraging to perform further research into mapping the role of cognitive functions and socio-emotional development in dreaming, and also emphasizing the importance of pluralism in dream assessment. Furthermore a deliberate characterization of the neurophysiological correlates of children’s dream behavior is also desperately needed. As we saw in the introduction, data in this field are scarce and contradictory, but results from nightmare studies and the hints of dream feature changes during preadolescent ages show that such investigations could be fruitful, increasing our knowledge in both neural and dream development. Based on hints from adult psycho-physiological studies, we believe that low neural connectivity and immature REM sleep eyemovement patterns are potential sources or correlates of the reported simplicity of children’s dream reports. Although we need more research on whether REM sleep eye-movement patterns or sleep EEG measures are correlated with the peculiarities in children’s dreams. There is also a lack of data on potential correlations between maturational measures of human sleep and the ontogeny of dreaming.

By revealing the core features of developmental and psychophysiological emergence of dreams our level of knowledge would increase in the fields of dream and developmental neuroscience and also contribute to the better understanding of the deep layers of human consciousness.

Research agenda

Since developmental patterns of dreaming are still divergent in the literature, more empirical research is needed for further clarification of this area.

1) Further characterization of the correlates of children’s dreaming and dream narratives, focusing not only on the cognitive abilities but also on the socio-emotional status and development (with special interest in the processing abilities of emotional stimuli).

2) Studying the neurophysiologic maturation as the basis of development in dreaming and dream narratives.

3) Revealing potential correlations between maturational measures of human sleep and the ontogeny of dreaming.

4) Further investigation of nightmares and possible background cognitive-emotional adjustment in childhood.

Practice points

When investigating children’s dreams we have to be careful about:

1) The methodological biases resulting in divergent outcomes, especially in case of young children (three- to five-year-olds).

2) Preschool children’s dream narratives might have the special feature of using one single narrative aspect to refer to a whole story (due to difficulties separating symbols from represented objects). This phenomenon might be most prominent in emotionally loaded dream experiences such as nightmares, resulting in a highly restricted account of nighttime experiences, thus making diagnosis difficult (for example nightmare versus pavor nocturnus).

3) Although results are divergent between and within age groups, the striking stability of findings on nightmares and their relationship with emotional disturbance/traumatic conditions proves the importance of emotional processing during sleep and dreaming. This should be recognized in pediatric sleep medicine and child psychiatry.

4) Parallelisms between neural changes and dream patterns in adolescent age direct our attention to the importance of general neural information processing and maturation in dreaming.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the 2010 Research Grant of the BIAL Foundation (55/10) and the Hungarian National Scientific Research Fund (OTKA-K105367).

Appendix A. A short summary on theories of dreaming with a particular focus on their developmental relevance

Here we aim to shed light on some of the main theoretical and conceptual frameworks of the psychophysiological emergence of dream experiences, with a special emphasis on their relevance on the ontogeny of dreaming. Our presentations are not focusing on the details and theoretical debates related to the particular theories. The reader can find relevant information on these aspects in the reference cited in the text.

1) Freudian dream theory. The Freudian topographical model is one of the early significant conceptual frameworks which try to explain the phenomenology of dreaming [34]. The model postulates that the normal waking flow of psychic energy from the perceptual to the motor subsystems is hindered during sleep (mainly because of inhibited motor output). The waking flow of psychic energy is presumed to be modulated by unconscious wishes and memories. Recent memories, called day residues are instigating these unconscious wishes during sleep, which e taken the fully inhibited motor output e results in the inverted flow of the psychic energy: from the unconscious wishes and memories to the perceptual side of the psychological system. This inverted flow is hypothesized to result in vivid imagery which manifests itself as dreaming. The structural side of the model (currently known as the disguisee censorship model) emphasizes the incompatibility between the psychological representation of unconscious wishes and the normative-moral rules governing the superego functions. This incompatibility is hypothesized to be worked out by the application of censorship on dream content and it is presumed to be accomplished by disguising the wishes and related representational contents. The disguised contents become unrecognizable and the resulting representations and plots bizarre. Thus, complex, bizarre dreams are mainly caused by the superego, which develops relatively late during ontogeny. Accordingly, children’s dreams are short and simple, while the underlying wishes can be easily recognized by the external observer. These predictions were supported by Freud’s early examples on children’s dreams as well as by some of the empirical research work reviewed in our paper. However, the overall level of simplicity and lack of bizarreness are still debated in the literature (see also the methodological issues detailed in the main text of our paper).