|

Page 4 of 7

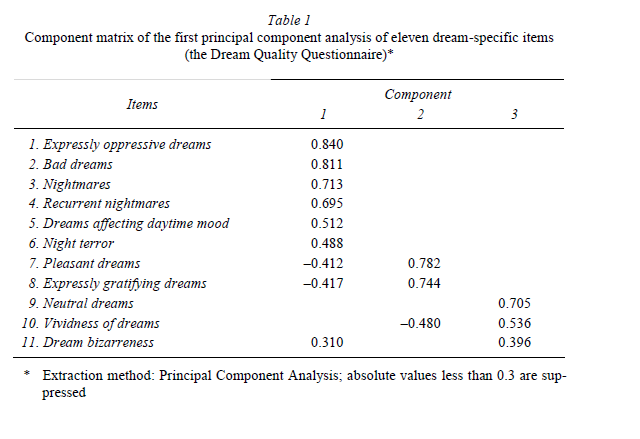

3. Results3.1. Factor structure of the Dream Quality QuestionnaireTo examine the latent structure of the 11 dream-specific items, we conducted a principal component analysis. Calculations resulted in the extraction of 3 components with eigenvalues greater than one, which accounted for 54.8% of the score variance (Table 1).

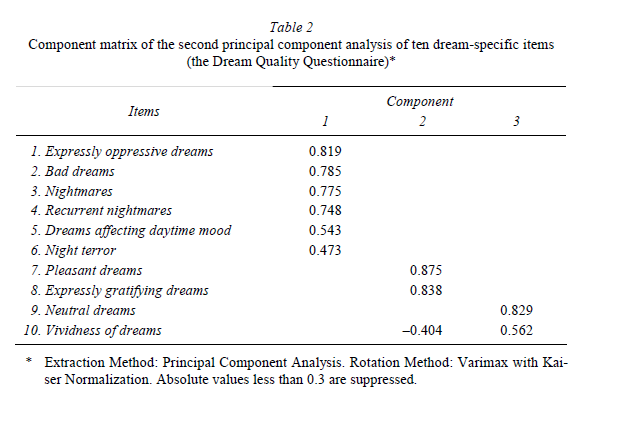

Since the Bizarreness of Dreams item was loaded almost equally on components 1 and 3, and as such cannot be decided to which component this item belongs, in the next analysis we excluded this item, and conducted a Varimax Rotation of the remaining items. With the exclusion of the Bizarreness of Dreams item, the explained variance increased to 59.3% (Table 2).

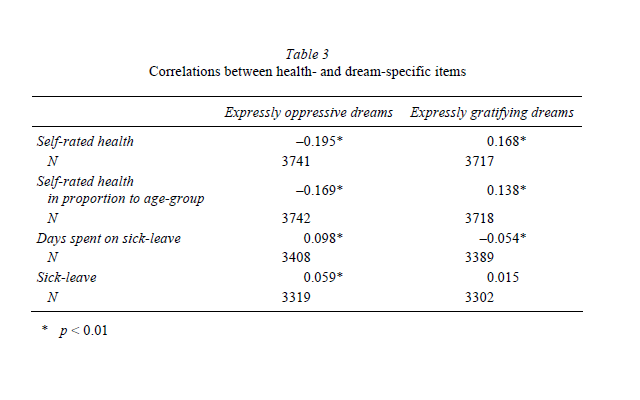

It can clearly be seen that items from 1 to 6 are forming component 1, and measure negative emotional load of dreams. Although this is not absolutely evident for item 5 (Dreams affecting daytime mood), the results cohere with the potential long lasting effect of disturbing dreams, the phenomenon of so-called nightmare distress. Component 2 unambiguously consists of two items (7 and 8) measuring the emotionally positive aspects of dreams. In component 3 two items (9 and 10) can be found, which measure emotionally neutral aspects of dreaming. 3.2. Interrelations between dreams and healthIn the following section we present the results of our preliminary analyses conducted with the Dream Recall Frequency Scale and some relevant items of the Dream Quality Questionnaire focusing on the interrelationship between dreaming and health. There was no significant relationship between dream recall frequency and health indexes. We now focus our attention on expressly oppressive dreams, expressly gratifying dreams, recurrent and non-recurrent nightmares and night-terror-like symptoms. As we can see in Table 3 almost all the general health indicators correlated with the emotional load of dreams in the expected manner and direction. The frequency of oppressive dreams correlated with negative self-rated health and a worsening in the state of health. The expected positive correlation between the days spent on sick-leave and dreams with negative emotional charges were supported but in this case only a weaker relationship was found. The correlations between positive emotional dream charges and health-indicators follow the expected directions but with slightly lower values than in the case of negative dream charges.

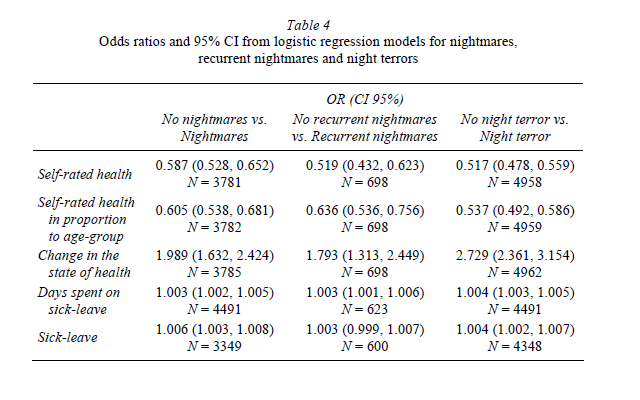

In order to investigate the relationships between the dichotomous dream-specific variables (nightmares vs. no nightmares, recurrent nightmares vs. no recurrent nightmares, night terrors vs. no night terrors) and quasi-continuous health-specific variables we conducted a series of logistic regression analyses. Odds ratios (OR), the upper and lower limits of their 95% confidence intervals (CI) in parentheses and the number of cases included in the analyses are indicated in Table 4. Note that odds ratios close to 1.0 indicate that unit changes in that independent (health-specific) variable do not affect the dependent (dream-specific) variable. Since there is no case where both upper and lower confidence limits are not with the same sign (here positive), we can consider all results as significant. Some remarkable associations were found between change in the state of health and frequent nightmare experiences. The worse one’s state of health becomes, the higher his/her chances are for frequent nightmare experiences (OR 1.989), recurrent nightmares (OR 1.793) and night-terror-like episodes (OR 2.729). Regarding days spent on sick-leave (OR between 1.003 and 1.006) it can be said that they do not affect the appearance of these nocturnal phenomena.

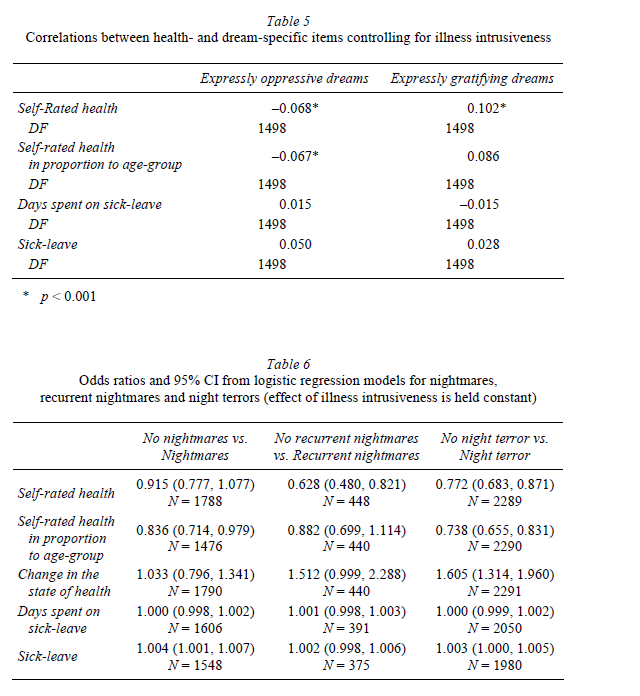

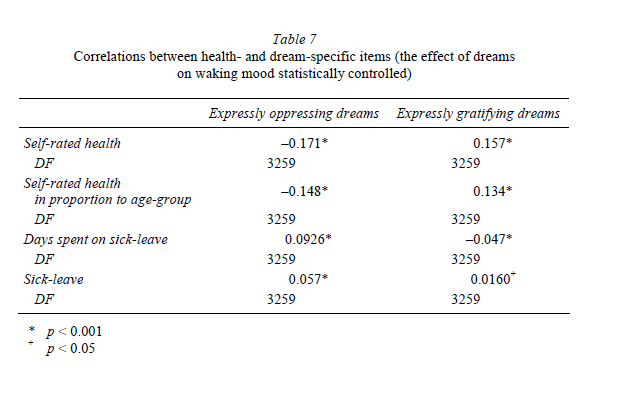

While interpreting the above results, we have to keep in mind that in this crosssectional study, information on dreams and on health were collected at the same time, hence the correlation can result from the fact that the diseases and the subjective difficulties – causing problems of adaptation –, negatively affect the emotional aspects of dreams. Although this possibility does not contradict our hypothesis, we consider it an important question, because it may shed light on the causal relationship of the examined phenomena, and it is also relevant from a practical point of view. Therefore, in the following statistical analysis we took into consideration the values of the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (NOVAK et al. 2005). We aimed to clarify whether the relationship between the negative emotional load of dreams and a worse health state reflects simply the stress and the hardships caused by the diseases, or whether there is a more general relationship between dreaming and the predisposition to illnesses. Illness intrusiveness evidently relates to the emotional aspects of dreaming. Taking into consideration these relations, we re-examined our data (T A substantial decrease in the magnitude of correlations suggests that these relationships are attributable in some part to illness intrusiveness. The relationships between self-rated health and dreaming remained significant for both oppressive and gratifying dreams but, when checking for illness intrusiveness, emotionally positive dreams show a stronger relationship with one’s state of health, opposite to that seen without the statistical control for the illness intrusiveness. We conducted the same analyses (dreaming – health relationship with illness intrusiveness statistically controlled) for the dichotomous items of the Dream Quality Questionnaire (Table 6).

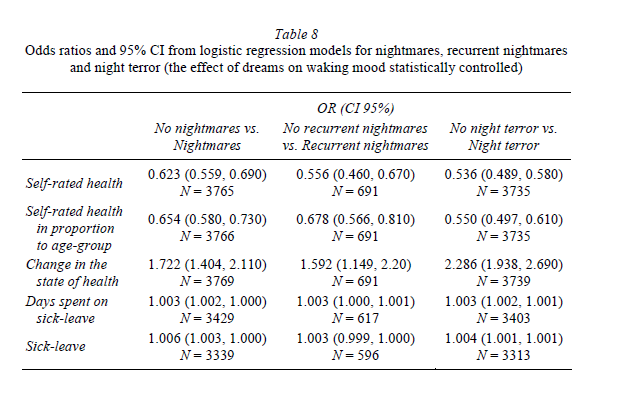

3.3. Effects of dreams on daytime moodEven by their sole existence, emotionally negative dreams can prejudice the mental state, and the physical-mental well-being of the dreamer. Otherwise, the nightmares and some forms of fearsome nocturnal awakenings (night terrors, sleep panic attacks) would not belong to the sleep and/or psychiatric disorders that require medical treatment. The next step was to reanalyse the relationships between dreaming and health by taking into account the effect that dreams exert on waking mood. This was done in order to test if the residual daytime effects of bad dreams per se explain the negative self-rated health associated with bad dreams (Table 7).

As we can see in Table 7 almost all the general health indicators correlated with the emotional charge of dreams in the expected manner and direction. Although the correlations are lower than without control for any variable (see Table 3), the results indicate that after controlling the effect of dreaming-induced daytime mood a significant correlation between health indicators and items measuring the emotional charges of dreams still remains significant. The same analysis was performed for the dichotomous variables (Table 8). We found a similar pattern of associations to those introduced above (see Table 4). Note that in this case variables measuring sick-leave seem to be the most independent of dream-specific variables, and a change in the state of health (i.e. worsening) proved to have the strongest relationship with nightmares and night terrors. 3.4. Dreams and well-beingAccording to our theoretical introduction, dreams reflect the psychological balance of the individuals. In order to test this issue empirically, we examined the relationship between the items assessing dream quality and the items aimed to measure well-being.

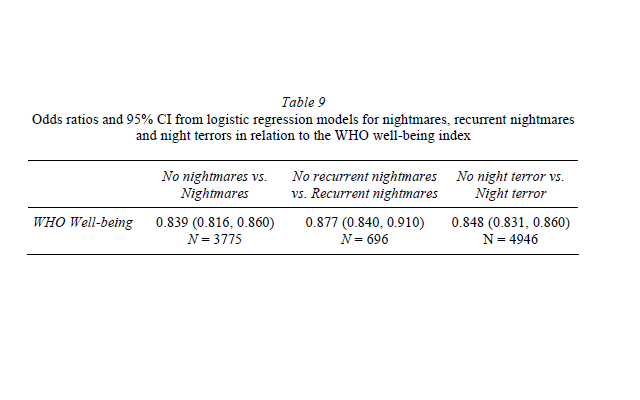

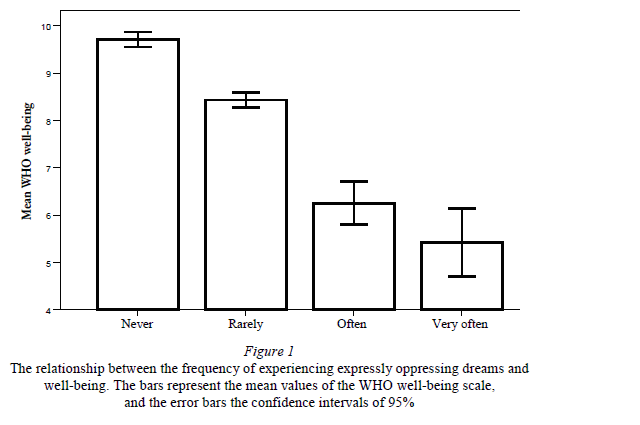

The frequency of expressly oppressive dreams was inversely related to the well-being scale of the World Health Organization (WHO). One-way analysis of variance resulted in F = 129.84; p < 0.0001 (see Figure 1). As expected, the frequency of expressly gratifying dreams was positively associated with well-being (one-way ANOVA: F = 56.079; p < 0.0001). The relationship between dichotomous items and well-being was analysed by logistic regression. Frequent non-recurrent and recurrent nightmares and night-terror-like symptoms were associated with a lower level of well-being (Table 9).

The above results suggest a particularly strong relationship between the emotional aspects of dreams and the well-being of the subjects. In our theoretical introduction we suggested that the information obtained from dream mentation could give us a more precise picture about the mental state of the individuals than the direct questions concerning the mood or well-being, because the latter could be biased by the expectations of the subjects.

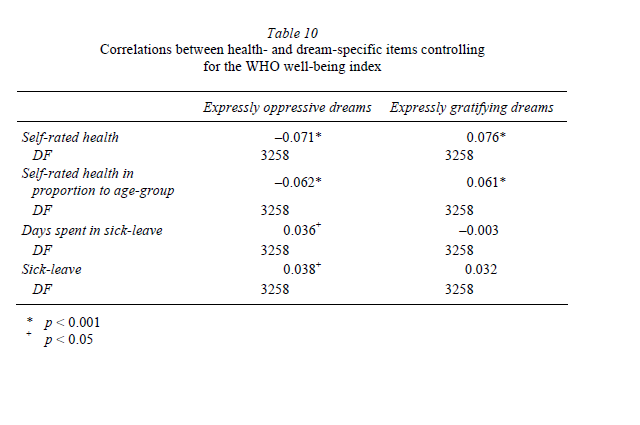

Physiological evidence suggests that the self-rated well-being index may influence the state of physical health (BÓDIZS 2006). At the same time – as we have seen – well-being is related to the emotional aspects of dreams, but this connection is far from being perfect. Thus, the emotional dimension of dreams reflects some other factors, which are unrelated to the directly rated wellbeing. We tried to show this difference in relation to the health indexes. We examined the relationship between health and dreams, taking into consideration that this relationship could partly be mediated by well-being. We wanted to know if dreams reflect the state of health equally like well-being or if dreams also provide other information that could be interesting. Our statistical analysis partially supported the latter possibility (Table 10).

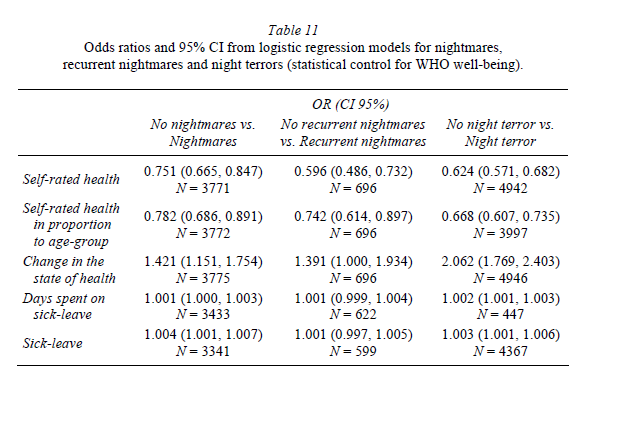

Other dream variables which were dichotomous in nature were also correlated with self-rated health measures, while the effect of the WHO well-being index was statistically controlled (Table 11).

|