A clear diagnosis of cancer can only be made by histological examination, making the report one of the most important documents in the life of a cancer patient, but its contents are not readily understandable to most people. The second workshop of the C80 project at the Institute of Pathology and Experimental Cancer Research, Semmelweis University, led by pathologist Richárd Kiss, discussed the incongruities of this situation, the reasons for it and the content of a histology report.

A histology report is about the patient, his disease, and thus, in fact, his fate. The findings will determine whether it is actually cancer, a malignant process or something else, possibly just a banal abnormality. Even in the case of a known cancer diagnosis, a histology report after surgery will determine whether further surgery is necessary, whether additional chemotherapy is needed or whether there is a possibility of other treatment, even targeted therapy.

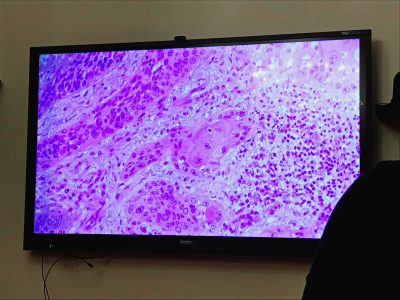

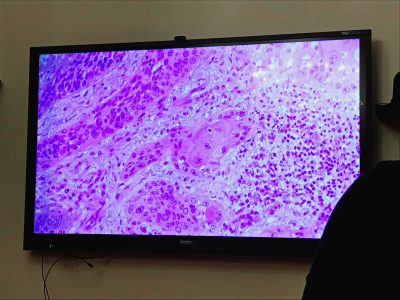

The information contained in the histopathology report is therefore crucial and intimate, if only because of the nature of the examination, as the pathologist examines tissue from the patient’s body and uses his or her eyes to look through a microscope to see structures that are not kept hidden. The image seen is always somewhat unique, but it follows the laws of the human body’s structure and the way diseases work. The pathologist uses these laws and disease characteristics to determine which disease fits the picture. In this sense, the pathologist is in fact answering a question posed by the patient’s doctor, the clinician.

In his question, the clinician summarises the patient’s history, symptoms, the circumstances of the sampling and may also give a guiding diagnosis depending on the situation. This information is included on the request form that accompanies each histopathology specimen. The clinical information and questions on this form are repeated on the histology report, as it must contain all the information on the basis of which the pathologist has made his decision. This is followed by a macroscopic description of the specimen, i.e. what the pathologist sees when he or she holds the specimen, its nature, size, shape, anatomical localisation. Here the pathologist also notes information on where to cut out the parts of a larger specimen or surgical material that are particularly relevant to the disease and where it will be further examined microscopically. Next is the microscopic description, where the pathologist describes the microscopic image seen on the histological sections taken, with particular reference to the characteristics of the pathological lesions. Logically, this section may also include the results of additional investigations. These include immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry or various genetic tests. These descriptive sections, which do not yet contain definitive conclusions, are essentially pieces of a jigsaw puzzle from which the pathologist puts together the picture in the opinion and diagnosis boxes. The opinion field is optional and is filled in for cases that are complex or require explanation for some reason. Here, the pathologist describes how he/she has arrived at the diagnosis based on the above information, what possible questions remain, but also makes suggestions to the clinician or provides further explanations, for example, on the behaviour of rare diseases. Finally, under the diagnosis, the pathologist will give the official name of the disease, as defined by the WHO for tumours, and any other clinically relevant additional information. This may include the grade and stage of the tumour, molecular genetic abnormalities, immunohistochemical profile, or information on whether the tumour tissue was removed completely, intact, during surgery.

At this stage, the histological findings use precise categories, abbreviations and special notations that are known to clinicians but are usually not understood by patients. The reason for this is that the purpose of the report is to answer the clinician’s question, so it is essentially a channel of communication between doctors, but it is of course about the patient. As the histology report is also a patient record, which is the property of the person concerned, it is also uploaded to the Eletronic Health Record systems, so the patient often reads it before the doctor. This can of course lead to a lot of tension, stress and misunderstanding, because as well as the fact that the patient may find a lot of unintelligible parts of the report, seemingly straightforward terms such as tumour may also have a different medical meaning to what the lay reader thinks. These terms and phrases, often misinterpreted or distorted in common parlance, are the subject of the following workshop at C80.

C80 is part of the project “Tackling the taboo of cancer through contemporary art: an integrative education programme that explores the universal human experience of cancer.” funded by the EUniWell (European University of Well Being) Seed Fund. The project is led by Semmelweis University in a consortium with the University of Florence, the University of Murcia and Linnaeus University.

If you find it interesting, share it!