Dr. Katalin Suszták, Professor of Medicine and Genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, held an impressive presentation on recent results of cellular and molecular nephrology research in EOK titled „Single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney reveals potential cellular targets of kidney disease”. The internationally well-known professor – she earned her MD and PhD degrees at Semmelweis University and has been living in the US for more than 20 years – was one of the keynote speakers of the international ERA-EDTA Congress in Budapest. We asked her to tell us about her life and career path as a Semmelweis Alumni in the United States and how she became one of the most acknowledged and prominent scientists of nephrology research of the world.

Professor Suszták graduated from the Medical Faculty of Semmelweis University in 1995. Her interest for science showed already during the university years: she was a student researcher at the Institute of Physiology, doing research under the supervision of Professor Erzsébet Ligeti and András Kapus and obtained her PhD degree at the Doctoral School of Molecular Medicine. She moved to the US together with her husband in June 1997. Today she is Professor of Medicine and Genetics at the University of Pennsylvania. Work in her laboratory aims to gain a better understanding of molecular pathways that govern chronic kidney disease development. Dr. Suszták was the recipient of the 2011 Young Investigator Award of the American Society of Nephrology and American Heart Association, one of the most prestigious awards given to researchers under the age of 41 in the field of nephrology.

You moved as a freshly graduated medical student to the United States. What were your plans for the future?

Since phagocytes, blood and immune cells had been the focus of my research in Hungary, my interest turned first towards malignant diseases of the blood. However, it shortly became clear that oncology was not for me. At the beginning of my Internal Medicine specialist training in the U.S., I started my internship at an intensive care unit which was a huge challenge for me. The quick, problem-based and practice-oriented American medical approach was very different from the analytic thinking that I was used to during my university years in Hungary. However, combining this type of thinking with my analytical mindset turned my professional career to the current and right direction from one moment to another.

What happened?

After my first month of internship, when – to be honest – I was already about to give up internal medicine, a paralyzed patient with low Potassium levels was brought to the ICU. Making use of my kidney physiology knowledge gained at Semmelweis University, I explained to my fellow doctors in detail what was going on in the patient’s body pointing out that a genetic mutation in the kidney might have changed the proton secretion and contributed to that health condition. The consulting nephrologists were really impressed by my explanation. For them, this approach was very unusual, as young American doctors usually made a diagnosis based on the symptoms and did not reanalyse the entire renal transport physiology in such detail.

What do you think your different approach was due to?

Thanks to my student research experience and PhD studies, I was able to approach problems differently, such as those people know who had the opportunity in depth research experience. Although in the first few months that I spent in America, I felt a bit of a disadvantage because Hungarian medical education was less practical than the American medical training, my analytical thinking and research experience compensated for this and in the end as you see, I have managed to catch up.

How did you get into nephrology research?

Following the patient interaction, I was immediately invited to join a kidney research group, where I stayed and worked for the next 7 years. I finished the 3-year internal medicine internship, and the specialty training in nephrology (2 years) and I have spent most of my time in the laboratory. There was no way back: I simply fell in love with the science of nephrology. It was 1997, and everybody said that the future was human genetics so my interest turned toward this exciting area. We started to collect and sequence kidney samples, creating a 30-piece kidney tissue bank. We examined the whole genome, studying how chronic kidney disease develops on the molecular level and identified very interesting correlations. In 2012, my family and I moved from New York to Pennsylvania, where I work at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania as Professor of Medicine and Genetics today.

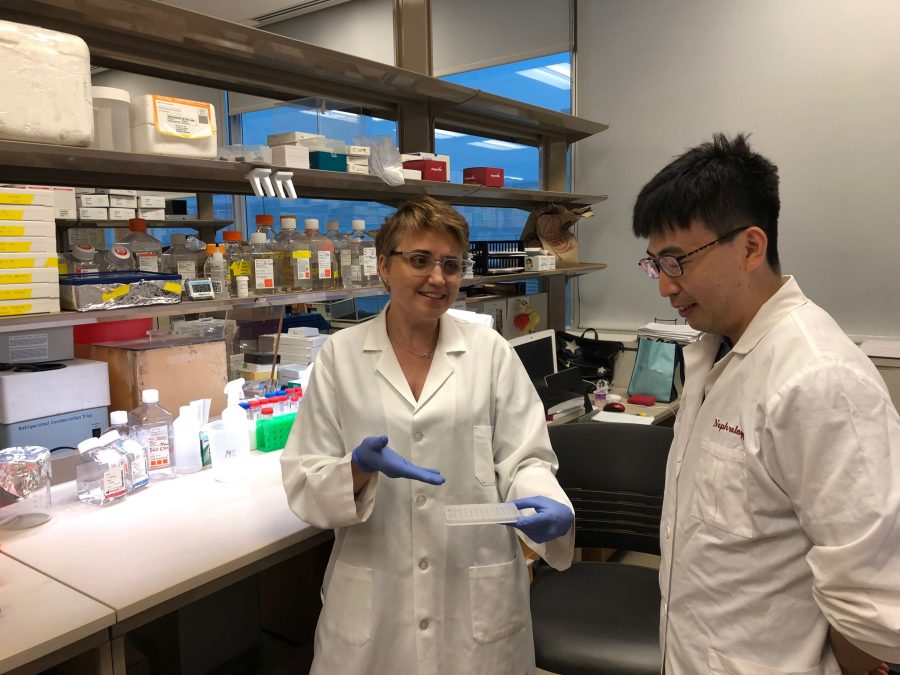

What is in focus of your scientific work at the Suszták Lab?

Basically working around the same questions as before, but our opportunities have grown significantly thanks to the development of technology and medicine. Since one key bottleneck to progress in this field has been the lack of well-characterized human tissue samples, we established the largest human kidney tissue bank with over 3000 kidney samples and launched longitudinal patient cohort studies. It is amazing how modern technology widened our possibilities – while in 1997 our tissue bank of 30 samples was a great achievement, today we have one hundred times more samples available. In our Lab, we are doing research aimed at understanding molecular pathways that govern chronic kidney disease development, with special emphasis on diabetic and cardiovascular-related kidney disease which are responsible for about 75% of cases.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a condition in which the kidneys are unable to clear waste products. The disease affects close to 10% of the population worldwide, which means 700 million people globally. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are both risk factors of Chronic Kidney Disease and are strongly intertwined since DM can lead to both CKD and/or CVD, and CVD can lead to kidney disease.

We mostly do systematic and unbiased analyses to find out which genes and cells are responsible for the development of vascular and diabetic kidney disease. An emerging technology called single-cell transcriptional profiling allows us to monitor global gene regulation in thousands of individual cells and answer central questions in kidney biology and disease pathogenesis. We have found that genetically distinct kidney diseases with common clinical features share common cellular origins. Which means that there might be a strong connection between chronic kidney disease’s symptoms and the mutations of certain cells. It is a very challenging field, our scientific results are really encouraging and we have a great research team which is always motivating.

What positive outcomes can your research have for everyday people suffering from chronic kidney disease?

If we are able to identify which cells and genes are responsible for certain symptoms, we can make a huge step towards finding the cure for these diseases which is our ultimate and most important goal, of course. We are now in the phase of systematic analysis of the correlation between cells and symptoms, but on the longer term we will be able to identify and target these cells by advanced therapy. Based on our findings we hope to be able to develop a new drug in the foreseeable future.

Your work is recognized worldwide and your scientific results are published in the most important international professional journals. Which are the recent ones?

Nature Medicine (Renal compartment–specific genetic variation analyses identify new pathways in chronic kidney disease), Science (Single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney reveals potential cellular targets of kidney disease) in 2018 and Nature Communications (Kidney cytosine methylation changes improve renal function decline estimation in patients with diabetic kidney disease) in 2019 are probably the most recent ones.

What was the purpose of your visit to Budapest?

I stayed in Hungary for a few days as the keynote speaker of the ERA-EDTA Congress held in Budapest.* In my keynote speech at the congress as well as in my recent presentation at Semmelweis University I introduced methods and summarized recent findings of our research, which is also described in detail in the mentioned publications. I am thankful for the invitation by Professor Erzsébet Ligeti and Dr. Zoltán Jakus and colleagues who made great efforts to organize my trip and program in every detail.

What does being a Semmelweis Alumni mean to you?

Semmelweis University is well known and highly acknowledged around the world. I am proud of being an Alumni of this university, and it is always nice to return to my Alma Mater, meeting colleagues interested in our research. I think that it is very important for Semmelweis University to make good use of its Alumni network. American universities are putting a significant emphasis on this. It is essential to show what people graduated from Semmelweis University have achieved. The Alumni’s success is also a success of the University, and when we are promoting our personal scientific results all over the world, we are all influencing the international reputation of the university as well. I think that it is especially important for current Semmelweis students and young doctors and scientists to see the Alumni’s success stories so that they can draw the conclusion that they can achieve almost everything if they believe in themselves and are persistent enough to follow their dreams.

What do you think is the main difference between the American and Hungarian medical education? What advantages and disadvantages can be identified? Semmelweis University is a huge institution compared to American medical schools. It is regarded as a hybrid system somewhere between an American medical school and a college. In America, students do the basic subjects like physiology in college and then they continue in a medical school where the training is very practical. Medical students do almost everything: they perform biopsies, they intubate and do operations, so they have more practical experience at the time of graduation than Hungarian students do – this was a significant difference between me and the American students at the beginning.

I think that practice-oriented medical training is very important and I am glad to hear that Semmelweis University’s curriculum reform is going in this direction. However, there are two sides of every coin. When the training is too practical – such as the American – it becomes harder to be creative and analytical. They see symptoms and tell the diagnosis. What’s interesting and exciting in this? With the introduction of artificial intelligence, more and more tasks will be taken over from doctors by IT systems. No doubt: computers can follow algorithms better than us. What these systems cannot substitute is the ability of creative and analytic thinking that only the human brain is capable of. Human thinking is what really matters and medical education should encourage that. So, I believe that the Semmelweis University is going in the right direction: practical training based on strong theoretical foundations is the key to high level and competitive medical education.

What advice would you give to medical students, young doctors and scientists?

To always be curious, stay motivated, and never forget or be lazy to analyse the situation. Make use of the numerous opportunities university offers. Extracurricular activities offer great possibilities that students do not even realize sometimes. It is a great advantage that medical education is free for Hungarians. I would encourage them to do student research (TDK) and PhD research since these are good ways to prepare themselves for a scientific and/or medical career.

How do you spend your days in America?

I spend most of my time in the laboratory but I am also taking part in the care of nephrology patients at the hospital and in the education of rotating medical students. Beyond these, I am travelling quite a bit to different destinations as I often receive invitations to international conferences and professional meetings. We have many Hungarian friends in the USA, we meet each other regularly. There are many Hungarian doctors living in America and the Hungarian-American medical society is very cohesive.

What will be the first thing you do when you return to the USA?

First of course I am excited to see my family, but I am also an avid gardener. I’ll see how my pepper and tomato seedlings are doing in our backyard and how much they have grown. Unfortunately, deer often pick them before us, it is difficult to keep them away. But since we have built a fence they are in security. And the fruit trees – my mother planted several beautiful trees for us. We have pears and peaches – I hope that we will have a nice harvest this year.

Zita Dékán, Faye Gillespie

Photo Credit: Dr. Katalin Suszták

* The prestigious international event of Nephrology returned to Hungary after more than 30 years and was organised in cooperation with ERA-EDTA and the Hungarian Society Nephrology.